TITANIC’s CENTRE PROPELLER: DOSSIER

This dossier groups together everything you might wish to know – in one place.

For decades, it was simply assumed that Titanic‘s propeller configuration was the same as her sister Olympic‘s. This assumption became accepted as fact.

The evidence we have available today is to the contrary:

- Harland & Wolff’s records for the completed Titanic state she had an increased pitch on the port and starboard propellers, as well as an enlarged diameter centre propeller with three blades instead of four. These records came to light in 2007, when Mark Chirnside was researching the Harland & Wolff records supported by Jennifer Irwin, and were made publicly available in an article published in 2008;

- The papers of a turbine specialist working for John Brown & Co., who were subcontracted to build Olympic and Titanic‘s turbine engines, strongly support the Harland & Wolff evidence. These were uncovered by Joao Goncalves and made publicly available in 2020.

Our interpretation of history is not static. Historical research is always ongoing and historians are obliged to adapt their views to take into account new evidence. Titanic artist and visual historian Ken Marschall noted in April 2023:

it’s inevitable we’re going to keep learning more things, new information is going to keep emerging about Titanic…

This dossier groups together everything you might wish to know – in one place.

Resources at a Glance

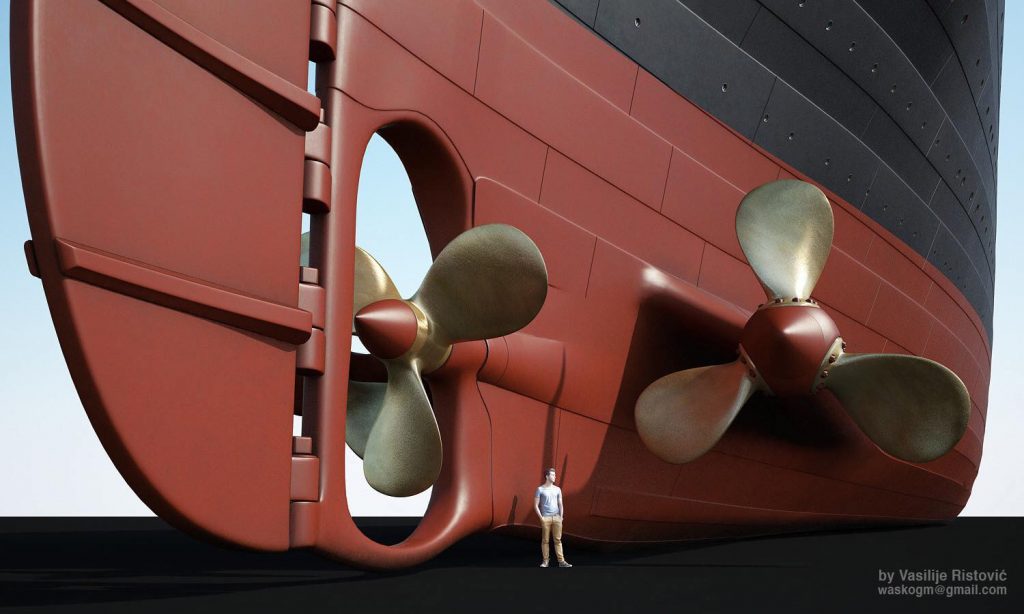

Above: An artist’s illustration of how Titanic‘s propeller configuration appeared, based on the Harland & Wolff documentation which came to light in 2007. (Courtesy Vasilije Ristovic, 2019)

Above: An artist’s illustration of how Titanic‘s propeller configuration appeared, based on the Harland & Wolff documentation which came to light in 2007. (Courtesy Vasilije Ristovic, 2019)

Mark Chirnside’s presentation outlining the primary source evidence for Titanic‘s centre propeller configuration (viewing time 30 minutes): ‘Titanic at 110: Learning, Unlearning & Relearning History’ (April 2022)

In April 2022, Mark Chirnside presented a lecture at Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI) for the Belfast Titanic Society. At 29 minutes 22 seconds, he went through the key evidence concerning Titanic‘s propeller configuration in detail, document by document.

Much of the material concerned is included in various articles published since 2008:

‘The Mystery of Titanic‘s Centre Propeller’ (2008)

Evidence from Harland & Wolff’s records show that Titanic was completed with a three-bladed centre propeller.

This article outlined the discovery of primary source documentation from Harland & Wolff with Titanic‘s propeller specifications. Their records state that:

- Titanic‘s port and starboard propeller blade pitches were increased and

- that her centre propeller was enlarged, with three blades instead of four, compared to Olympic’s 1911 configuration.

In hindsight, the use of the word ‘mystery’ in the title is rather over-dramatic, because the Harland & Wolff evidence is clear that Titanic had a three-bladed centre propeller. It is the best source material we have. Unfortunately, familiarity bias (the tendency to believe what we already believe to be true) can be hard to overcome. Prior to that time, everyone apparently accepted the assumption she had a four-bladed centre propeller without question, yet since 2008 nobody has been able to provide any evidence at all to support that assumption.

Titanic‘s Centre Propeller: The Stephen Pigott Evidence (2020)

Evidence that proposals for both a three-bladed and four-bladed centre propeller were under consideration c. 1910.

This article analysed a discovery by researcher Joao Goncalves of a notebook in the papers of Stephen Pigott, a turbine engine specialist who worked for John Brown & Co. The Clyde shipbuilder was subcontracted by Harland & Wolff to work on the low pressure turbines for Olympic and Titanic and they shared their experience and turbine technology with them.

The notebook in Pigott’s papers includes two proposed centre propeller configurations for the two White Star liners: a three-bladed and a four-bladed one. These are identical to the centre propeller configurations for each ship in the Harland & Wolff records, in terms of the propeller diameters and the area of the propeller blades. (The sole difference is that the pitch of the propeller blades was changed on the completed ship).

‘RMS Titanic Reflections: Deep Conversations Episode 1’ (2021)

In this video (49 minutes 27 seconds in), Bill Sauder discusses the evidence concerning Titanic‘s centre propeller configuration and explains the nature of propeller design in 1912. Bill has spent almost forty years researching the ship and he is the Director of Research for RMS Titanic Inc.

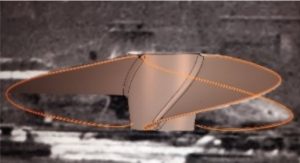

The Object On the Barge – Part 1 (2021)

‘What is lying on that barge is a three-bladed propeller…’

Sam Halpern’s article analyses ‘The Object On the Barge’ photographed in February 1912. His article includes 3D CAD models – the result of painstaking work by Tony Taylor – of the four-bladed centre propeller Harland & Wolff recorded for Olympic and the three-bladed centre propeller Harland & Wolff recorded for Titanic. The models are based directly on the recorded specifications.

How do these models match up with the object in the photograph? Sam concludes: ‘What is lying on that barge is a three-bladed propeller that happens to line up nearly perfectly with the three-bladed CAD model built in accordance with Harland & Wolff design specifications regarding number of blades, diameter, pitch and blade area for Titanic’s center propeller’.

The Object On the Barge – Part 2 (2021)

The propeller in the photograph is ‘amazingly close’ to the three-bladed propeller specified for Titanic.

Sam Halpern’s follow up article includes an analysis of the photograph to try and ascertain the size of the object on the barge.

His central conclusion in this piece is that the propeller in the photograph had a diameter of 16.95 feet. This dimension ‘is amazingly close‘ [author’s emphasis] to the 17-foot diameter of Titanic‘s centre propeller specified in Harland & Wolff’s records.

‘On A Sea of Glass 111 Anniversary Livestream with guests Ken Marschall and George Behe’ (2023)

In a segment of this video (about 43 minutes in), Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton, Ken Marschall and Bill Wormstedt discuss some of the reaction to the new discovery about Titanic‘s propeller configuration and the need for researchers to be open minded to analysing evidence.

‘Olympic’ Class Ship Propeller Specifications 1911-14:

| Port and Starboard Propellers | Centre Propeller | Comment | |

| Olympic maiden voyage configuration | Diameter 23 feet 6 inches Pitch 33 feet Blades 3 Blade Area 160 square feet |

Diameter 16 feet 6 inches Pitch 14 feet 6 inches Blades 4 Blade Area 120 square feet |

Olympic‘s centre propeller marked her as an exception. She was the only ship with ‘combination’ propelling machinery and a 4-bladed centre propeller that Harland & Wolff completed prior to 1914. |

| Olympic November 1911 configuration | Diameter 23 feet 6 inches Pitch 34 feet 6 inches Blades 3 Blade Area 160 square feet |

Diameter 16 feet 6 inches Pitch 14 feet 6 inches Blades 4 Blade Area 120 square feet |

The pitch of the port and starboard propeller blades was increased during the Hawke collision repairs. |

| Titanic maiden voyage configuration | Diameter 23 feet 6 inches Pitch 35 feet Blades 3 Blade Area 160 square feet |

Diameter 17 feet Pitch 14 feet 6 inches Blades 3 Blade Area 120 square feet |

The pitch of Titanic‘s port and starboard propeller blades was originally intended to be 34 feet 6 inches but was increased to 35 feet. |

| Olympic March 1913 configuration | Diameter 22 feet 9 inches Pitch 36 feet Blades 3 Blade Area 165 square feet |

Diameter 17 feet Pitch 14 feet Blades 3 Blade Area 125 square feet |

The diameter of Olympic‘s port and starboard propeller blades was reduced; the pitch was increased again to 36 feet; and the blade area increased slightly.

The diameter of Olympic‘s centre propeller was increased to match Titanic‘s; the pitch was reduced slightly; the number of blades changed from 4 to 3; and the blade area increased slightly. |

| Olympic July 1913 configuration | The Hampshire Independent reported that ‘occasion was taken to change her turbine propeller’ in July 1913. The specifications of the new centre propeller are unknown and the change is unconfirmed by primary sources. | ||

| Britannic September 1914 configuration | Diameter 23 feet 9 inches Pitch 35 feet Blades 3 Blade Area 160 square feet |

Diameter 16 feet 6 inches Pitch 14 feet 6 inches Blades 4 Blade Area 120 square feet |

The pitch of Britannic‘s port and starboard propeller blades was the same as Titanic‘s, however the diameter was increased by 3 inches compared to Titanic. Her centre propeller specification was identical to that of Olympic‘s original centre propeller. |

Source: All propeller specification data taken from primary source documentation in Harland & Wolff records.

Summary of data:

Although Titanic is one of the best-documented ships in history, there are some glaring gaps in our knowledge where researchers have previously been forced to rely on the assumption that her configuration was identical to her sister Olympic. Plenty of areas of the ship were not photographed. Titanic’s propellers were not photographed after installation. Photographs of her older sister are often used as a substitute, but they are not always captioned clearly enough to explain that they are Olympic images which have been used to stand in for Titanic. The consequence has been a great deal of confusion. Simply doing a Google search for ‘Titanic‘s Propellers’ produces plenty of images which are Olympic or, even worse, other ships entirely!

Until 2007, everyone apparently assumed Titanic’s centre propeller was the same as her sister ship Olympic’s.

A NEW DISCOVERY (2007)

Until 2007, everyone apparently assumed Titanic’s centre propeller was the same as her sister ship Olympic’s: a four-bladed configuration, in contrast to the three-bladed propellers on the port and starboard side of the ship.

However, that year I became aware of a Harland & Wolff engineering notebook that recorded the engineering particulars of each successive ship they completed, including their propelling machinery and propeller specifications. This was the result of researching Harland & Wolff’s records at Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI), assisted by Jennifer Irwin. The notebook recorded Titanic’s propeller specifications in detail and stated clearly that she was fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller. It also gave details of tweaks to Olympic‘s propeller configuration during 1911 and early 1912. It is the only primary source which records the number of blades on Titanic‘s centre propeller. This information was made available in an article, ‘The Mystery of Titanic’s Centre Propeller’ published in the Titanic International Society’s Voyage journal in 2008 and subsequently online at Encyclopedia Titanica.

There is, in truth, no ‘mystery’.

EIGHT YEARS LATER (2016)

In many ways, the wording of the original article comes across as somewhat hesitant. Looking back, I recognise my own familiarity bias: There is, in truth, no ‘mystery’. Since the article was published, nobody has come forward with any photograph that might have existed in a private collection of Titanic’s propellers after installation or any primary source documentation to contract the Harland & Wolff records. In fact, the new information that has become available only reinforces the conclusion that she was fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller. What became very clear was that the four-bladed centre propeller configuration was merely an assumption which people had come to accept as fact.

TWELVE YEARS LATER (2020)

Joao Goncalves’ discovery of a notebook in the Stephen Pigott papers demonstrated that both three- and four-bladed centre propeller designs were being explored for Olympic and Titanic while both ships were under construction. The two design proposals are virtually identical to the centre propellers fitted to each ship according to Harland & Wolff’s records, with identical diameters and area of propeller blade – the sole difference is that the pitch was adjusted subsequently.

REFLECTIONS…

It had always been understood by researchers such as Bruce Beveridge that Olympic was fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller during her 1912-13 refit. At a presentation at Belfast in April 2015, Simon Mills shared an early Britannic reference of her with a three-bladed centre propeller. There should, therefore, be nothing surprising or extraordinary about Titanic being fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller.

Shipbuilders of the period were constantly seeking to find the optimal propeller design to combine efficiency, benefiting speed and fuel economy, and minimal vibration, benefiting passenger comfort. A good example is all the changes Lusitania and Mauretania underwent during their early years of service, not to mention the changes to Olympic (and Titanic’s) port and starboard propellers as the shipbuilder adjusted the pitch of the blades. (Olympic carried three different propeller blade pitches on her port and starboard propellers between her completion in May 1911 and the end of her refit in March 1913.) Britannic‘s port and starboard propeller specifications were different, yet again.

Whatever the pros and cons of the three-bladed centre propeller’s performance on Olympic, it seems any benefits were outweighed by the negatives. She subsequently reverted to a four-bladed configuration and Britannic was completed with a four-bladed centre propeller as well. This is confirmed by Harland & Wolff’s records; is visible in period film from 1914, and can be seen on Britannic‘s wreck today.

We now have evidence that all three ‘Olympic’ class ships were either:

- fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller (Titanic);

- fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller for a period (Olympic); or

- contemplated with a three-bladed centre propeller at an early stage in construction (Britannic).

As Bob Read has written:

For those who are reluctant to accept a three bladed centre propeller on Titanic, they must consider the fact that there is absolutely no evidence that Titanic ever had a four bladed centre propeller‘. [my emphasis]

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q. You said that there are no known photos of Titanic’s propellers fitted, but there are many in books and online.

A. Unfortunately all these claims are incorrect. The original photographs taken for Harland & Wolff by R. Welch (1859-1936) were all given a unique reference number. The details of each glass plate negative were recorded alongside the reference number, including a description of the subject of the photograph and the date that the photograph was taken. By looking up the contemporary reference numbers, it’s possible to identify the photographs taken of Olympic’s propellers, including when they were fitted in 1911, when a blade from the port side propeller was being replaced in March 1912, and when she was at Belfast for an overhaul in January 1924.

These Olympic photos are well-known and have been used in books, websites and documentaries to stand in for Titanic. The captions rarely make it clear. Unfortunately the fact that they are Olympic photographs tends to go unnoticed. (In fact, the 1924 photograph is one of the most famous: it shows shipyard workers standing on the dry dock floor with Olympic’s three enormous propellers towering above them. It is often used to illustrate Titanic and it appeared on an enormous banner promoting the salvaged Titanic artefacts when they were displayed in Amsterdam in 2013-14, but few people realise it was an Olympic photo taken 13 years after Titanic sank!)

There were also physical differences between Olympic and Titanic in 1912, which confirm the photograph reference numbers. There was a small zinc plate fitted above the centre propeller aperture: on Olympic, it had eight rivets but on Titanic it had only five. This is clear in early Titanic construction photographs before her propellers were fitted.

Q. But every depiction of Titanic shows her with a four-bladed centre propeller? James Cameron’s film, for example.

A. Until 2007 it was perfectly reasonable to assume Titanic had a four-bladed centre propeller just like Olympic. However, historians have to be open-minded and change their views to reflect new evidence. Instead of mere assumption, we have primary source evidence from Harland & Wolff about Titanic‘s propeller configuration.

Q: The wreck has been explored, photographed and filmed – doesn’t this provide an answer?

A. Although the port and starboard propellers were forced upwards when the ship’s stern slammed into the ocean floor, Titanic’s centre propeller is buried in the seafloor. The wreck is therefore of no assistance unless a future expedition is able to explore beneath the mudline.

Q: I’ve been interested in Titanic for years and I’m reluctant to accept this because I’ve never heard of her having a three-bladed centre propeller?

A. It is natural that many people will have a bias towards the familiar. Many people have accepted an assumption (the four-bladed centre propeller configuration) as fact, yet question the three-bladed centre propeller even though it’s based directly on primary source evidence from the shipbuilder’s own records. Historians need to adjust their interpretation of history to take into account new evidence. The emergence of new evidence is inevitable. As artist Ken Marschall said in April 2023:

I’ve painted the four-bladed propeller on more than two or three occasions and so yeah, I suffered a little bit too when I first started hearing well, we think it really had three blades. And my first reaction was “no, come on”. You know I didn’t want to go there because it makes my paintings wrong but that’s the evolution [of Titanic research], I mean it’s inevitable we’re going to keep learning more things, new information is going to keep emerging about Titanic…’

Q. What does it matter?

A. The issue here is that, if we’re writing about history, we need to try and get the facts right. It might seem there is little or nothing more to learn, but how many other beliefs are merely assumptions which have become accepted as fact through the years?