FAQ: Was Titanic’s Starboard Propeller Used to Repair Olympic after the Hawke collision?

No.

The available evidence indicates that Harland & Wolff used three spare blades as replacements for the three damaged blades on Olympic’s starboard propeller.

George Cuming, one of Harland & Wolff’s managing directors, was one of a number of professionals to see Olympic in drydock. On 14 October 1911, he summarised the necessary repair work to an Engineer Commander, whose report went to the Director of Dockyards (on behalf of the Admiralty) some days later.

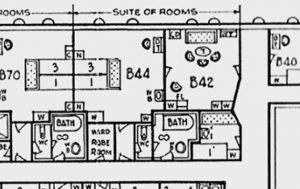

Olympic’s Starboard Propeller Blades

There was some good news: ‘There are no marks on the propeller blades of the centre and port shafts to show that these have been touched by anything at the time of collision’. Unfortunately, the starboard propeller blades were all damaged:

The three blades have been removed; they are damaged towards the tips. They are probably bent as well although this is not obvious. Mr. Cummings’ [sic] proposal is to scrap these three blades, appropriate three spare and replace the spare blades used. The blades are…manganese bronze.

Olympic’s Starboard Propeller Boss

The starboard propeller boss itself (the cylinder at the centre of the propeller to which the blades were attached) was ‘apparently undamaged’ but either of Titanic’s port or starboard propeller bosses were available to use as a replacement in the event that any damage to Olympic’s starboard propeller boss became apparent later. (There is no evidence that it did.) Harland & Wolff proposed to ‘anneal the studs for securing the blades, and if necessary, to renew them’. (To ‘anneal’ meant to heat the material and then allow it to cool slowly, which made it easier to work. In the event, it was necessary to renew at least some of them.)

Olympic’s Starboard Propeller Shafting

There was damage to Olympic’s propeller shafting, but Harland & Wolff did not think any bent shafting could be straightened out or repaired. Instead, it would need to be replaced:

The tail shaft can be withdrawn into the dock and so removed to the shop, the three pieces forward of this necessitate that certain plates should be removed from the ship’s side so as to pass them out into the dock and so send into the shop.

Where the shafting passes through [watertight] bulkheads, the plating has had to be cut in order to uncouple and pass the shafting to be removed through the orifice being cut in the ship’s side.

It is not expected that these four lengths will be in the shop for another seven or eight days, and so the renewal necessary as regards them is unknown. As a precautionary measure a forging has been ordered for one length of shafting. The shafting is hollow and Messrs. Harland & Wolff do not consider that if any length is bent it can be made serviceable by straightening.

The Titanic’s shafting is available if necessary but if used would entail considerable delay in that ship’s completion, as the engines are now being put into her.

While Olympic was in dry dock, Harland & Wolff took the opportunity to increase the pitch of her port propeller blades from 33 feet to 34 feet 6 inches. The cost was accounted for separately to the repairs of the collision damage. The new starboard propeller blades were undoubtedly set at the same pitch.

Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room has been overhauled to improve the user experience on mobile devices, make it easier to order books and generally refresh it for the 2020s. All credit for the work goes to

Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room has been overhauled to improve the user experience on mobile devices, make it easier to order books and generally refresh it for the 2020s. All credit for the work goes to