Titanic‘s Collapsible A: Oceanic‘s First Officer Sights the Lifeboat Adrift, May 1912

This and many other incidents from Oceanic‘s interesting career are chronicled in Oceanic: White Star’s ‘Ship of the Century’ (signed copies are available for purchase through this website).

On 8 May 1912, every one of Oceanic’s lifeboats was ‘lowered into the water and tested’ before she left Southampton for Cherbourg, Queenstown and New York. At Cherbourg, ‘Madam Navratil, mother of the two French waifs from the Titanic now being looked after in New York’ boarded. She was one of 736 passengers, including only 61 in first class.

Five days later, Oceanic was well on her way to New York and steaming through a moderate swell with light southerly winds. First Officer Frank sighted a boat to starboard in latitude 38˚ 56’ North longitude 47˚ 01’ West around 12.45 p.m. Captain Smith ordered the ship stopped and she came to rest about 800 yards away. Then the emergency boat was lowered in charge of the fourth officer, John Withers. As word spread throughout the ship that the boat contained bodies, ‘passengers of all classes lined the rail’ to watch what was happening. One month after Titanic’s sinking, the boat turned out to be her collapsible A lifeboat: one of two collapsible boats that floated off the boat deck in the ship’s final moments as her frantic crew ran out of time to launch them.

Withers returned and reported that the bodies were ‘not in a fit condition to be taken on board, and recommended that they be buried from the boat they were in’. Dr. French was called to identify them and then Bo’sun Jones ‘volunteered to go and sew them up in canvas, as he had been a sail maker and had had experience in burying men in the Red Sea and other places in the East’. Oceanic’s flag was lowered to half mast as Dr. French read out the service and Captain Smith, his officers and crew ‘stood to attention bareheaded on the upper deck with the passengers, who followed their example’:

As the doctor uttered the words ‘We commit these bodies to the deep’, the sailors let the three canvas covered bodies sink beneath the waves, and the boat pulled back to the Oceanic towing the Titanic’s boat astern.

By the position the boat was found in she must have drifted seven and three-quarter miles a day…

Smith recorded what happened in the ship’s log:

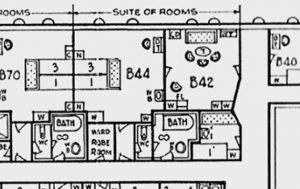

Three bodies were found in the boat but being decomposed and unfit for removal these same were committed to the deep from the boat, service being read by Doctor French. One presumably was the body of Thomson Beattie, identified by name on pocket lining of coat, the others, a sailor and firemen respectively. A fur lined overcoat was found in the boat and letters in pocket addressed to Richard Williams, also two rings welded together as one inscription on inside of one ‘Edward & Gerta’ on the other ‘Edward’. Ship proceeded at 2.27 p.m. having taken on board collapsible boat which is marked No 1. Deck lifeboat certified by Board of Trade to carry 47 persons.

American newspaper reports (below) suggested subsequently that ‘the three men had lived for several days and died of starvation after devouring the cork in the lifejackets’. White Star officials and Dr. French were quick to deny the suggestion ‘emphatically’.

Above: One of a number of sensationalised newspaper reports which falsely claimed that people who had initially survived the Titanic disaster subsequently ‘starved’ to death. In reality, they were already dead when Collapsible A was set adrift. (New York Evening World, May 1912)

Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room has been overhauled to improve the user experience on mobile devices, make it easier to order books and generally refresh it for the 2020s. All credit for the work goes to

Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room has been overhauled to improve the user experience on mobile devices, make it easier to order books and generally refresh it for the 2020s. All credit for the work goes to