FAQ: A Sound ‘Like a Cannon Shot’ – Why Did Majestic Crack?

On the night of Sunday 14 December 1924, the White Star liner Majestic (1922) was running through heavy seas en route to New York when a sound ‘like a cannon shot’ rang out. Incredibly, the C-deck plating had fractured from the inside of the second funnel uptake on the starboard side, running right across the deck, past the second funnel uptake on the port side and out to the ship’s side. The fracture then continued through the heavy plating at the side of the ship (the sheer strake) and partly down the ship’s side. It was particularly serious because C-deck formed the ship’s strength deck and the sheer strake plating at the side of the ship was also specifically strengthened.

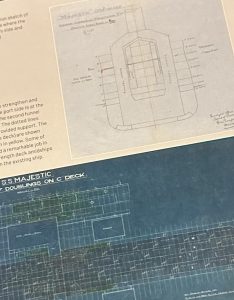

Above: Detailed blueprints and surveyors’ sketches showed the full extent of the damage and subsequent repairs (see RMS Majestic: The ‘Magic Stick’). The sketch seen at the top of this extract, above, gives an idea of the split funnel uptake arrangement. Unlike a traditional configuration with the ship’s funnel uptake extending directly upwards amidships, the designers chose to split the funnel uptake into two – one on the port side and one on the starboard side – to allow for spacious passenger accommodation amidships.

What had caused the problem?

The issue is explored in detail in RMS Majestic: The ‘Magic Stick’, however multiple factors were considered by the naval architectural firm Roscoe & Little, as well as the Board of Trade surveyors. She had been designed and built in Germany by Blohm & Voss. Roscoe & Little understood that the ship had been running at a deeper draught than her builders originally intended, increasing the stresses on the hull by 7-8 percent. (They put forward several schemes of repair work, one of which would simply restore Majestic to her original strength, but the White Star Line and Harland & Wolff thought this was inadequate because it would leave her 20 percent weaker than Olympic, which was taken as a benchmark example of a strong ship.)

The Board of Trade were surprised to receive test results on samples of the steel plating removed from Majestic‘s sheer strake. They revealed a ‘surprising deficiency’ in the material’s ultimate tensile strength, because the steel bore a stress of only 23.2 to 25.4 tons. The replacement plating was tested to 32.5 to 34.5 tons, which was in line with what it needed to be. The samples of the original material which were tested had been almost 30 percent weaker by comparison.

The Principal Ship Surveyor was concerned that the split funnel uptake design involved not just cutting into the strength deck plating twice, but that sufficient ‘compensation’ (additional strengthening measures) had not been included in the design to make up for it. The position of the ship’s lifts (elevators) was criticised and there were also ventilator openings at the corners of the funnel uptakes. The placement of the expansion joints also coincided with a weaker area of the deck. All of these features were far from ideal and served to collectively weaken the strength deck.

They did calculations which indicated that, owing to her greater weight and length, Majestic‘s tendency to bend (‘bending moment’ in naval architectural terms) was about 33 percent greater than Olympic‘s. This should not have been a problem because ship designers took into account a ship’s bending moment in the structural design of the ship, but Majestic‘s strength had not been increased to the same extent. She was, comparatively, significantly weaker. The North Atlantic passenger liners all encountered particularly severe storms in the winter months and she should have been able to withstand this, but a combination of all these factors and the fact that Majestic had been driven at high speed put such a stress on her hull that it lead to a serious structural failure.

She was out of service for repairs over the course of several months early in 1925. Harland & Wolff got to work effectively rebuilding the strength deck over a length about 233 feet. This work included substantially thicker steel plating on C-deck, with some areas of double plates replaced with treble plating and other areas which were originally single plating doubled up to provide greater strength. It set her up for more than a decade of further service!