Happy New Year – 2026!

Wishing you all a happy and healthy New Year!

It’s not every year that I post a ‘Happy New Year’ message, but it seems appropriate as we enter 2026.

2025 was a very busy period in so many ways. It’s great that the number of visitors to Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room increased by 115 percent compared to the previous year. New features such as ‘FAQ Fridays’ in July were very popular and I have had a lot of positive feedback from readers who have enjoyed the Frequently Asked Questions blog posts. They address common questions but also serve as a myth-busting tool, because they discuss topics which are often subject to inaccurate information and explain why that information is inaccurate, using the primary source evidence. Sadly, the reality of modern media and the internet is that inaccurate, sensationalised information so often goes viral, but putting the available evidence out there does go some way to remedying that for the discerning reader who values quality of information rather than quantity.

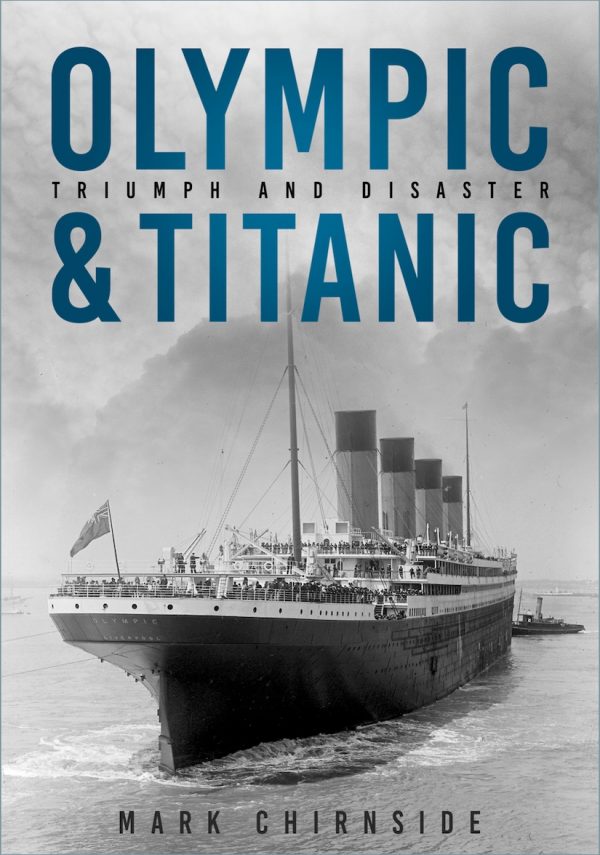

It was great to announce in September 2025 that the new book, Olympic & Titanic: Triumph and Disaster, will be published by the History Press in April 2026 (UK release). This book has been in the works for a long time but the completed manuscript was only submitted to the publisher at the start of May 2025.

It might be helpful to explain the process of taking a book from idea to reality.

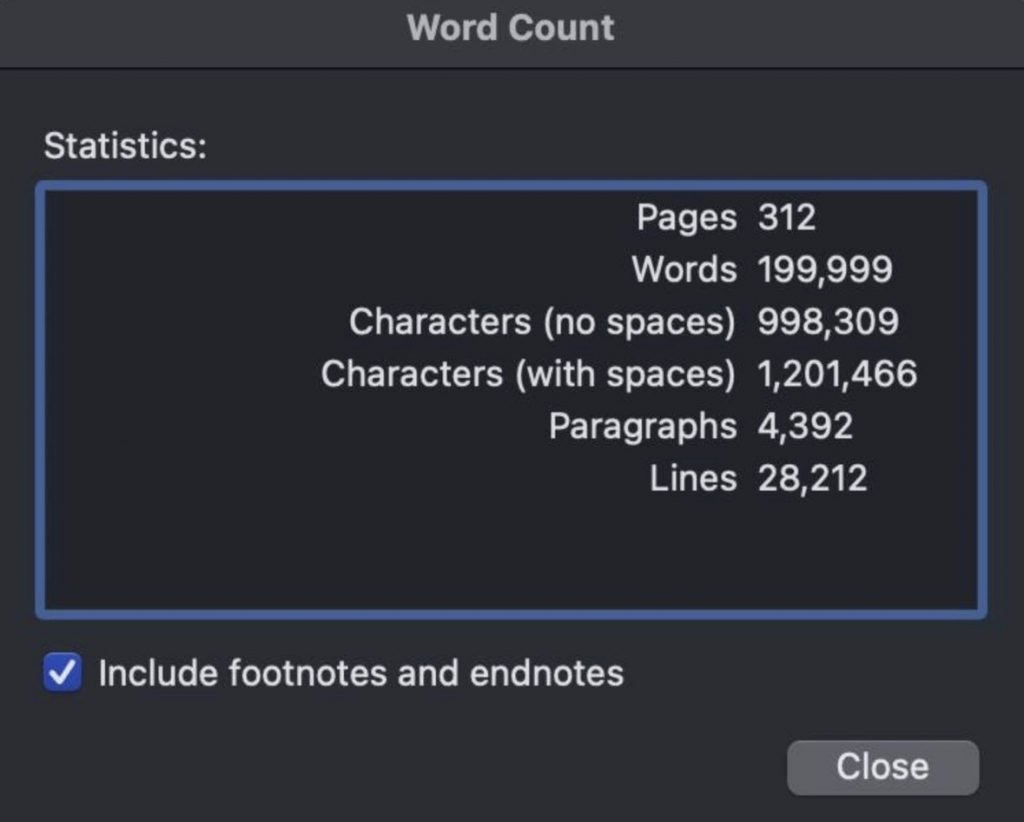

Authors are typically self employed and so each book project is written under its own contract and to a particular specification. The author and publisher will have already agreed a format (which might be a lavishly illustrated paperback book with fewer words or a large hardback book with a focus on the information in the text). Common practice is that there will be a range of tolerance for both the word count and the number of illustrations. For this book, the image count came in right in the middle of what had been agreed but the upper limit of the word count was 200,000 words. The finished manuscript ended up one word short!

The complexity of a project such as this is only appreciated fully by those directly involved. I was horrified to see I had burst through the maximum word limit and run to over 240,000 words. This entailed slashing the manuscript before it could even be submitted to the publisher. Cutting about 40,000 words required a disciplined editing effort on my part, but the end result was a sharpened focus on the key themes of the book. (To help visualise the extent of the cuts, these words are the equivalent of the Majestic book.) The cuts will not be wasted because they provide material for blog posts or articles in the future!

On submission of a book to the publisher, they will typically check over the manuscript and give it an initial read through to make sure that its content fits the original pitch. They will map out how it will all fit together in the finished product and how many pages will be required, taking into account the word count, number of images and intended use of those images. (As the author, I personally find it helpful to make recommendations concerning each image submitted. There might be some images which could be cut out if necessary, whereas another image might be rare or previously unpublished, meaning that it should be prioritised if space is at a premium during the book design process. In other cases, images are directly referenced in the main text itself so making sure that they are used in the final book is essential! The book designer will not necessarily be someone who knows the book’s subject and so it’s an important partnership between the author and designer to make sure we have a common understanding.) In the case of this book, although the word count was (just) within the upper limit and the image count was in the middle of the range, the page count rose from the projected 368 pages to 416 pages (plus the colour section). It’s a very big book!

Whipping the manuscript into shape typically involves a number of different editors. They might come back to the author with queries if they feel a certain statement is unclear, or where a section of a chapter might benefit from being restructured. In this case, I was relieved to hear that they thought the text was already in very good shape, but they made a number of recommendations which improved it a lot.

After months of work and queries back-and-forth, the author receives an initial set of page proofs to check over. This is where they see for the first time how the text and images have all been moulded together into the book design template by the design and editorial teams at the publisher. Proofreading is a mammoth task and usually involves multiple sets of page proofs. Initial comments / corrections are sent back to the publisher to be addressed; then a corrected set of page proofs is returned to the author to be checked and re-checked. It is amazing how many errors come to light only on the third read-through! A major challenge for the author is that they ‘know’ what they have written and so skim reading is not an option. It is a very tiring, focused process to try and read what is actually on the to-be-printed page rather than what the author thinks it says.

This book was researched and written over an extended period of time. One of my greatest pleasures was in learning new information about these ships from proof-reading my own book, because I ran across information again which I already knew but had slipped out of my memory! I benefited from the input of a number of colleagues who kindly reviewed sections of text pertinent to their particular expertise before the manuscript was submitted to the publisher. There were also others who were generous with their time and undertook pre-publication reviews based on the final product. Some of these reviewers came back to me with specific queries and in many instances I checked and re-checked the source material underpinning a particular statement. It goes without saying that any errors are the author’s ultimate responsibility.

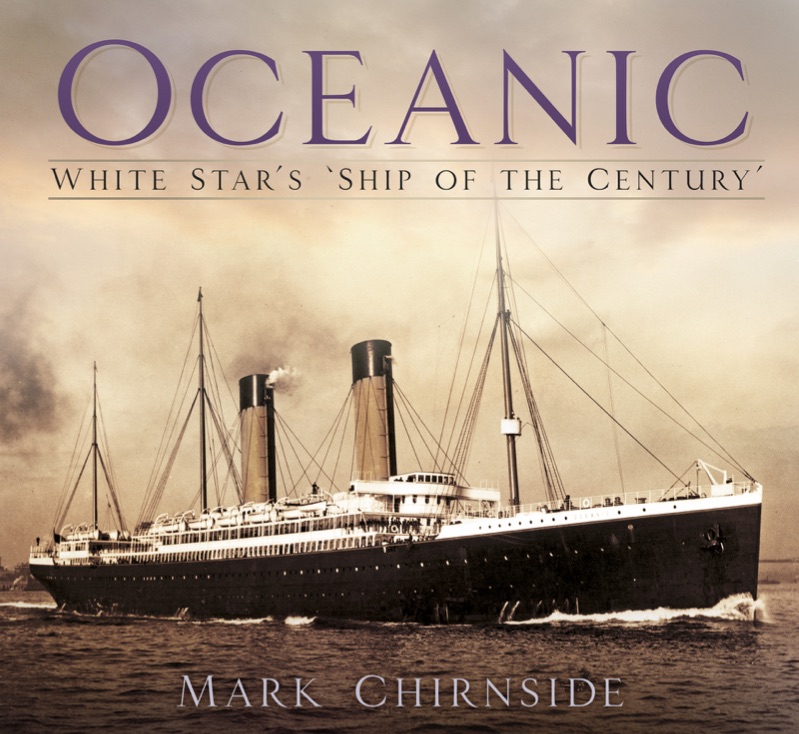

Each book brings its own challenges. My own experience is that there will always be something that is missed (hopefully a very small detail such as a comma being used somewhere instead of a full-stop), which can be frustrating given how hard all the individuals have worked to try and eliminate that sort of error. Way back in 2006, when the first edition of the Majestic book was about to be signed off and sent to the printer, I realised to my horror that the page headers with the book title had ‘HMS’ Majestic rather than ‘RMS’. It was a last-minute correction that saved a considerable amount of embarrassment!

In this case, one of the illustrations provided by a photo archive was incorrect. The image (supplied directly to the publisher) showed the first class reading room rather than the first class smoke room. Although the archive reference number I had provided for the image was correct and I had fully intended to use a smoke room image, a well meaning individual at the archive had noticed that the archive catalogue description for that image incorrectly referred to the reading room and they substituted the image for the ‘correct’ one. This necessitated sourcing the image again – and explaining that the ‘incorrect’ image was the one required!

Formatting rules can create complexity. Should a particular word be in italics or not? It’s often the case that foreign language terms (such as the name of a dish on a French menu) will be italicised. However, each publisher will have their own ‘house’ style guide to ensure consistency between all of their titles. Some terms which are now in widespread use in English language publications are no longer appropriate for italics but should be formatted in roman. Changing the formatting from the original manuscript to the text in the book design template can introduce inconsistencies if one term is changed but another is missed. Therefore, it’s essential during the proofreading stage to make sure that all terms are formatted the same way. In the case of original source quotations where I have emphasised a particular point in italics, it is always necessary to make sure that a notation has been included to explain it is the author’s emphasis (rather than the original source document) and that the italics made it through to the final book.

Ship names represent a particular problem. By convention, they are always in italics but the formatting can be lost when the original manuscript is being transferred into the book design template. The most obvious ones are easy to spot but reviewing the entire text to make sure any ship names have not been missed is always a challenge – and there is always one which will be missed.

Indexing presents its own challenge. Indexing the content of the book can only be done very late in the process, because the layout needs to be 99 percent complete. We need to have confidence that any page numbers will not be changing after the material has been indexed. The process is laborious, but essential to help readers locate the material they want and to do justice to the sheer quantity of information in the book. A whole series of decisions need to be taken. Firstly, a judgement call on which subjects should be indexed. Titanic is an obvious example of a subject which should be included, but such a large entry necessitates numerous sub entries beneath the main topic. My approach was to cover the basic generalities first, then focus on areas where the book presents particularly important or new research and information. Then there are other issues to consider – should a person’s title be used, or just their surname and first name? What should be done in those instances where someone’s title changed? For example, William James Pirrie only became a Lord in 1906. He appears in the book decades before he had the title. Then there are ship’s officers. If an officer was promoted and appears in the text in both their junior and senior roles, which should be used? Arguably, their most senior role, but it does create its own complications. To keep things simple, I ended up using the simple surname, first name and/or initials for people’s index entries. All of this minutiae might not be apparent to someone who picks up the book and skims the index for topics.

Another last-minute job is checking all of the cross references (‘see page X’), where the main text itself refers the reader to another section that is relevant, or to an image. In some cases, image captions also refer the reader to the main text. Again, the final page numbers can only be confirmed once we’re confident nothing is going to be moved around or deleted for any reason. For the final sign off before the book goes to print, the author and publishing team have to be as confident as they can be that no significant errors have been missed.

After weeks of intense collaboration on the page proofs, sending masses of corrections / comments back and forth, it was great to go on leave for Christmas, set the out of office email and drink some mulled wine!

What’s planned for 2026?

There are more FAQs and other blog posts in the pipeline. (If you have any suggestions for particular topics, do get in touch. It might not be possible to respond to each individually, but all will be considered.) April is naturally a busy Titanic month and you will see lots of new posts reflecting that.

Announcements about the new book and ordering options will all be published on this website – if you have not yet subscribed for regular updates via this blog, be sure to do so in order that you won’t miss out!