Article from the Archives: Britannic: A Glimpse from John Riddell’s Album

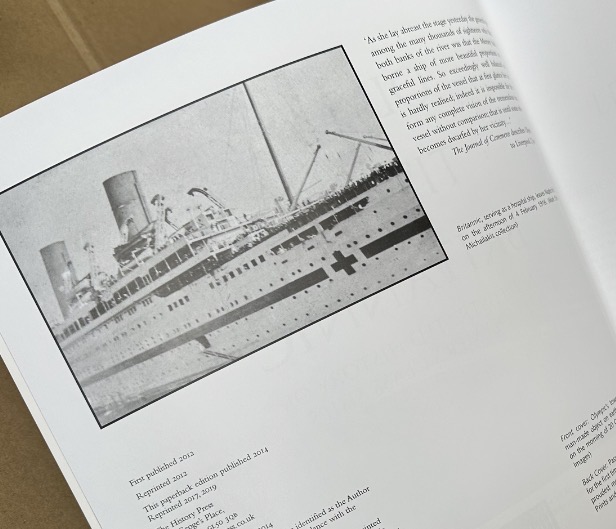

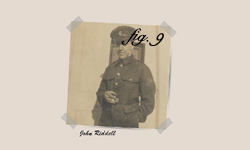

This post is from an article which was published originally on the Titanic Research & Modelling Association (TRMA) website in February 2008 by Mark Chirnside and Michail Michailakis. This was the first time that John Riddell’s many Britannic photos were made publicly available. Readers interested in Britannic can learn more about her history in Olympic Titanic Britannic: An Illustrated History of the ‘Olympic’ Class Ships , which includes Riddell’s images. Michail’s website is the leading online Britannic resource.

Britannic’s life was all too short. Consequently, researchers have access to far fewer photographs than they would like. As an added difficulty, during wartime the issue of security was very much at the forefront of the British authorities’ concerns. Nurses and Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) personnel were warned that the use of cameras was forbidden at the docks and it was technically illegal to photograph His Majesty’s vessels after 1914. Nevertheless, private photographs have survived and occasionally another photograph is discovered which adds to our knowledge of the ship.

Private John Riddell, of the RAMC, served onboard HMHS Panama during the war. He kept a photograph album which has survived to this day. The album has been identified by his own RAMC card, and a National Identity card issued during World War II which survived with the album. In early January 2008, the album was purchased by the present authors: Michail Michailakis and Mark Chirnside. It is a true gem, as it contains several rare Britannic photographs. We feel that these remarkable photographs – including four unique and apparently hitherto-unpublished images of Britannic – deserve a wider audience. Intriguingly, additional photographs of Mauretania and Aquitania have survived in the album, although – rather disappointingly for the Britannic researcher – two photographs that are captioned as ‘HMHS Britannic’ actually depict the smaller Mauretania!

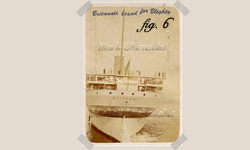

We know that four of them were taken when Britannic was preparing to leave, and then leaving, Naples (see Figures 1, 5, 6 and 7). Riddell captioned them specifically and there is nothing in the photographs to suggest that Riddell’s captions were mistaken. It is possible to identify when they were taken, right down to the hour, by examining several aspects of the historical record:

1: Draft

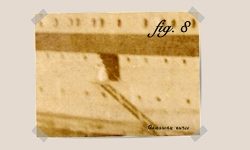

Although part of the stern is missing from the photograph (Figure 6), it is possible to estimate the ship’s draft using this photograph in combination with other images. We can then compare this estimate to the known draft each time Britannic left Naples, and this helps to narrow down the possibilities:

Draft of water aft at the time of proceeding to sea, on each Naples departure:

29 December 1915: 36 feet 1 inch.

4 February 1916: 34 feet 8 inches.

27 March 1916: 36 feet 6 inches.

1 October 1916: 36 feet 3 inches.

26 October 1916: 36 feet 8 inches.

19 November 1916: 36 feet 5 inches.

If the differences were merely a matter of inches, then this data would not be very helpful, but fortunately it is more than a foot. Britannic does not appear to be drawing any more than 35 feet, and so this narrows the date down to her 4 February 1916 departure.

2: Britannic at Naples

Britannic arrived at Naples for the second time in her career on 25 January 1916. She took on coal and water, before embarking patients from several smaller hospital ships between 27 January 1916 and 4 February 1916. She left at 3.15 p.m. on 4 February 1916, to return to Southampton.

3. Panama at Naples

His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Panama transferred 319 wounded to Britannic, between 9.45 a.m. and 11.45 a.m. on 4 February 1916. Riddell appears to have photographed Britannic when he was serving onboard Panama and, given that Panama had only arrived that morning, then it is likely the Britannic photographs were taken as she was leaving Naples at 3.15 p.m.

4. Aquitania at Naples

Two similar single-funnel vessels appear – one in a photograph of Aquitania (Figure 5a), and then another one in another photograph (Figure 5). However, the historical record shows that the Cunarder was at Naples around the same time as Britannic. It is known that Aquitania arrived at Naples on 7 February 1916. (She departed at 7.20 a.m. on 11 February 1916 and arrived at Southampton five days later.)

This information demonstrates that the photographs of Britannic were taken as she was departing on the afternoon of 4 February 1916, nine and a half months before she sank on 21 November 1916.

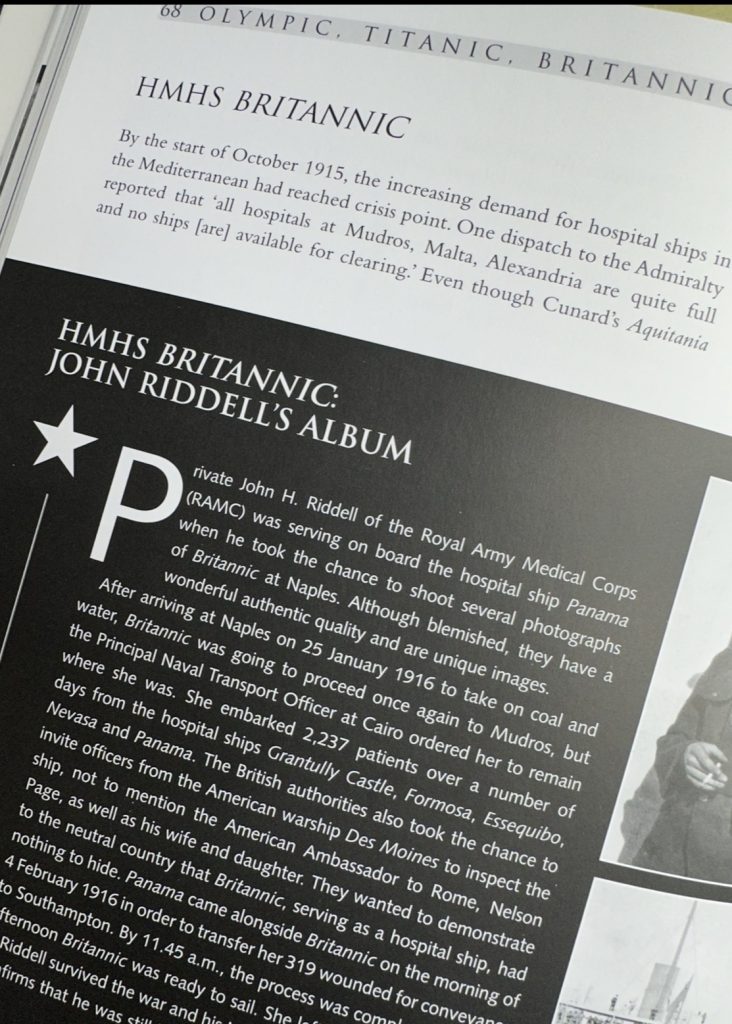

Above: Readers interested in Britannic can learn more about her history in Olympic Titanic Britannic: An Illustrated History of the ‘Olympic’ Class Ships .