Surviving the War: Celtic Torpedoed

This post is an edited extract from my article ‘Surviving the War: Celtic & Cedric, 1918′ which was published in the Titanic Historical Society’s Titanic Commutator April 2021: Pages 4 to 12. Readers interested in the ‘Big Four’ can learn about their history in The ‘Big Four’ of the White Star Fleet: Celtic, Cedric, Baltic & Adriatic .

Celtic left Liverpool under Captain Hugh David’s command early on 31 March 1918. One American and one British passenger were on board, along with over 320 crew, but no cargo. She left the Bar Light Vessel at 3 a.m., as per the sailing orders, but the escort failed to appear. The ship’s zig-zag course was altered by two points (twenty-two-and-a-half degrees) at five and ten minute intervals and she maintained a speed of about sixteen knots, working through the positions as ordered. At 7 a.m. her course was altered to North 16º West (magnetic). The weather was ‘overcast, squally, misty showers’ and with a visibility of ‘about two miles’. The force five wind was north-easterly.

Celtic (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division)

By 7.34 a.m., she was about eleven miles south-west of the Chickens Rock Lighthouse, off the Isle of Man. Unknown to the White Star liner’s crew, Wilhelm Meyer’s UB77 was lying in wait. His torpedo struck ‘on the port side in boiler room’ about twenty feet below the waterline, creating a ‘very large hole’ in the ship’s side. The boiler room filled instantly and shortly afterwards the engines stopped.

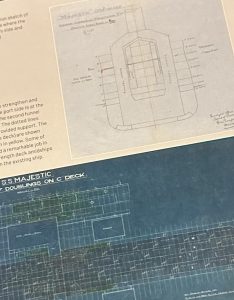

This segment from a longitudinal cross section through Adriatic’s engine and boiler rooms helps to illustrate Celtic’s internal layout, as well. Although this view is from the starboard side, it shows the aft boiler room where the torpedo struck (right) and then the reciprocating engine room (left). On both ships, the aft boiler room housed four double-ended boilers. (Copyright Bob Read, 2015)

A second torpedo passed astern, but went unnoticed on the bridge. Captain David acted quickly:

Alarm gongs were at once run as an emergency signal for boat stations, crew going to their stations at once. In view of the apparent limitation of damage and [the] ship’s headway no boats were lowered. Thinking that an alteration of course would be confusing to [the] submarine, I ordered helm hard a’port.

About fifteen minutes later, and twenty-six minutes after the first torpedo struck, the ship’s second officer and carpenter on the boat deck saw another torpedo approaching ‘at an angle of 45º on starboard bow’. Celtic’s speed was down to only three or five knots. It struck ‘nearly abreast of bunker hold [3] hatch on starboard side’ and the compartment was soon flooded.

The explosion was very severely felt on [the] bridge and vicinity, much more than the first which was well below water line.

The after gun position on the starboard side opened fire ‘with a view to keeping [the] submarine down and also attracting assistance’. HMS Scourge came into sight and was given the bearing of the submarine. Depth charges were dropped.

A diagram that shows the position of the two successful torpedo attacks in March 1918. Number 3 hatchway was just ahead of the bridge, very close to the watertight bulkhead that divided holds 2 and 3. It has been adapted from an illustration of Celtic that was published originally by Marine Engineering in 1901. (Author’s collection)

Celtic’s situation was getting worse by the minute. Three lifeboats on each side had been damaged by the explosions and Captain David feared that another torpedo attack was imminent, with his ship stopped and two compartments completely flooded. He ordered the lifeboats lowered away ‘without hurry, assuring all concerned that [the] ship would float for a long time’. About fifty crew were kept on board and confidential books and embassy despatches were sunk: these books had a weight inside them so that they would founder when they went overboard. HMS Prince arrived to screen Celtic’s port side and HMS Scourge also screened the ship from further attack. Despite serious damage and flooding, the ship remained afloat and stable, but the situation was precarious: she could not move under her own power and was vulnerable to any further attack, which would surely sink her. Furthermore, merchant ships that experienced mine or torpedo explosions sometimes suffered the after effects in further damage to their hull structure.

Sure enough, during the afternoon the engine room began to flood slowly and it became clear that the watertight bulkhead separating it from the boiler room was leaking. (Ironically, in the middle of the afternoon Wilhelm Meyer abandoned a further attack against Celtic because of apparent leaks in the U-boat’s hull.)

Scourge had already taken most of the ship’s company on (‘265 survivors’), but cast the lifeboats adrift ‘to keep up the screen round the ship’. The remainder of the crew were transferred to Prince. An attempt to take Celtic in tow failed because the cable proved too weak ‘and we abandoned further attempt for the night’. At 10.30 p.m. Scourge sighted HMS Dove and ‘gave her position of SS Celtic’.

Just before dawn on 1 April 1918, Captain David – who had spent the night on board Prince – went back on board Celtic with a small party. The weather moderated, the wind dying away and the sea calming down. The tugs Clevelys and Slieve Bawn ‘took us in tow starting out to get to the eastward of the Isle of Man’. Later that morning, members of the War Cabinet, meeting at 10 Downing Street, were advised by the First Sea Lord that she ‘had been torpedoed, and that the latest reports indicated that the vessel was still afloat. No troops were on board’. Around noon the tugs Harrington, Hornby and Herculaneum arrived and began towing. Good progress was made towards the land, but the tide was running to the west and so the tidal conditions compelled them to go westward. The engine room was ‘steadily filling’ and so it was clear that ‘some safe anchorage in shallow water was essential’ unless Celtic was going to join the long list of merchant ships lost during the conflict. At first, Port Erin seemed to be suitable but the outlying bank at Peel ‘afforded shoal water’ so it would be safe to beach the ship if needed.

Unknown to anyone on board, Wihelm Meyer had tried to attack again early that morning, but he was unable to. Later that morning, Carl-Siegfried Georg’s U101 was also on the scene: he observed Celtic being towed, about six or seven miles away. He waited, but was forced to dive when a destroyer came near. About twenty minutes later, he surfaced and saw additional vessels on the scene. Almost one-and-a-half hours passed and he dived, in an attempt to get closer, but it was already mid afternoon. Two depth charges were reported far away, and Celtic was visible: being towed by the stern by two vessels. At 8.48 p.m. on the U-boat’s clocks (perhaps about an hour ahead of Celtic’s), Georg ordered two torpedoes fired. They missed their prey, even though an explosion was reported and the sound of something breaking apart.

‘Ultimately we anchored at 9 p.m.’, Captain David recalled ‘…off Peel harbour in seven fathoms [42 feet], Sandy Bottom’. Salvage pumps were requested. The following day, at 9 a.m. the salvage pumps arrived with an Admiralty expert and they were put into operation in the hold, ‘becoming effective at 1 p.m.’ Prince’s crew had to assist to hoist in the pumping gear, because Celtic did not have enough crew left on board to do it without any steam power. Captain Bartlett, who had swum off the bridge of the sinking hospital ship Britannic in November 1916, arrived with Willett Bruce, the company’s superintendent engineer. Plans had to be made for temporary repairs, before permanent repairs could be carried out at Belfast. They would keep her out of service until autumn. However, if Celtic had survived a remarkable ordeal then it was already clear that a number of lives had been lost. Senior Fourth Engineer Stanley McDonald, 28, had been killed in the first torpedo explosion and Chief Boots Charles Jeffers, 46, had been killed by the second one. Firemen Samuel Routledge, 27, George Richardson, 21, and Trimmer William Gleave, 18, were also victims. (These men were buried in Belfast City Cemetery.)

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to David Hume Elkington for the header image, which is an early photograph of Celtic on a cruise in 1902. Many people shared their time, expertise and research so generously with me. Particular acknowledgement must be made to Sam Halpern and Oliver Loerscher.

Another example is a post I made recently on my

Another example is a post I made recently on my