Review It Yourself Podcast – RMS Olympic: Titanic’s Sister

It was great to discuss the revised and expanded edition of RMS Olympic: Titanic’s Sister (2015) with Sean on the Review It Yourself Podcast. Our episode is now live!

It was great to discuss the revised and expanded edition of RMS Olympic: Titanic’s Sister (2015) with Sean on the Review It Yourself Podcast. Our episode is now live!

The second of my two recent podcasts with Titanrick for Curiositanic is now available (recorded in English with Italian subtitles). We discussed the watertight bulkhead configuration, why the watertight bulkheads were designed as they were and whether this design was flawed. Another topic was the issue of Titanic‘s lifeboats and what happened to them. We also looked at Britannic‘s size and what her true dimensions were.

This interview is not only a journey into the past, but also an invitation to historical reflection: understanding the Titanic means contextualizing information, avoiding anachronistic judgments and analyzing technical decisions in light of their time, also emphasizing the importance of research based on official documents, fundamental tools for distinguishing facts from legends.

Wishing you all a happy and healthy New Year!

It’s not every year that I post a ‘Happy New Year’ message, but it seems appropriate as we enter 2026.

2025 was a very busy period in so many ways. It’s great that the number of visitors to Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room increased by 115 percent compared to the previous year. New features such as ‘FAQ Fridays’ in July were very popular and I have had a lot of positive feedback from readers who have enjoyed the Frequently Asked Questions blog posts. They address common questions but also serve as a myth-busting tool, because they discuss topics which are often subject to inaccurate information and explain why that information is inaccurate, using the primary source evidence. Sadly, the reality of modern media and the internet is that inaccurate, sensationalised information so often goes viral, but putting the available evidence out there does go some way to remedying that for the discerning reader who values quality of information rather than quantity.

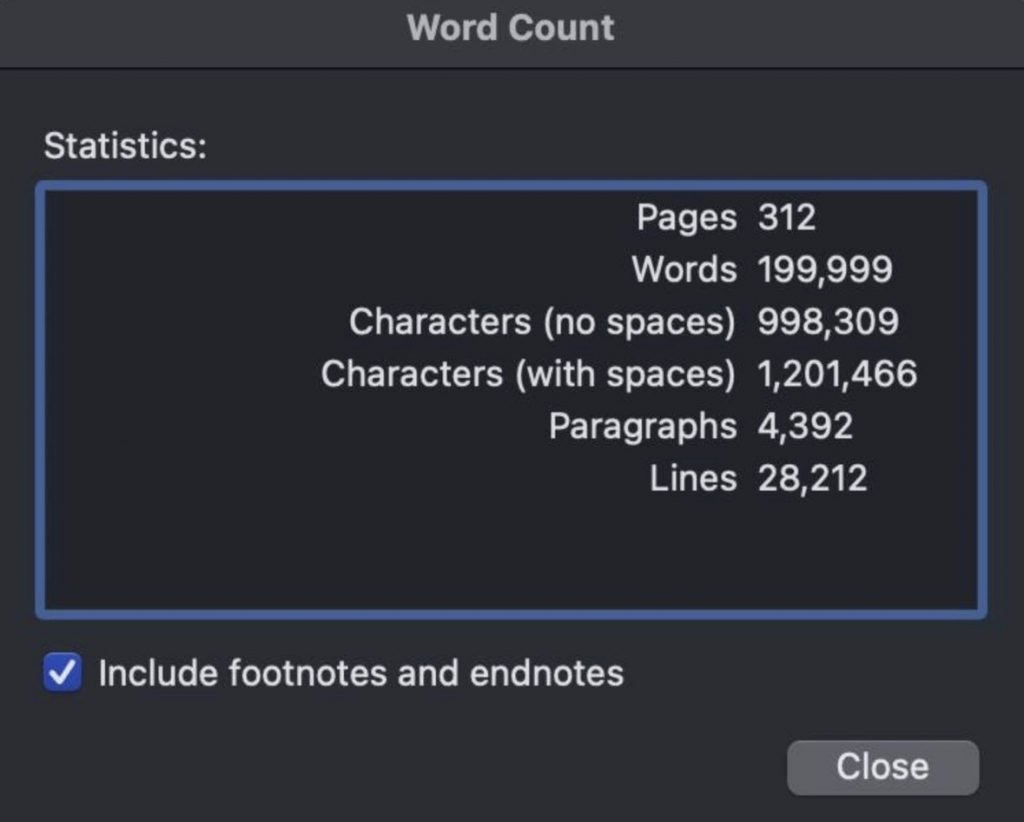

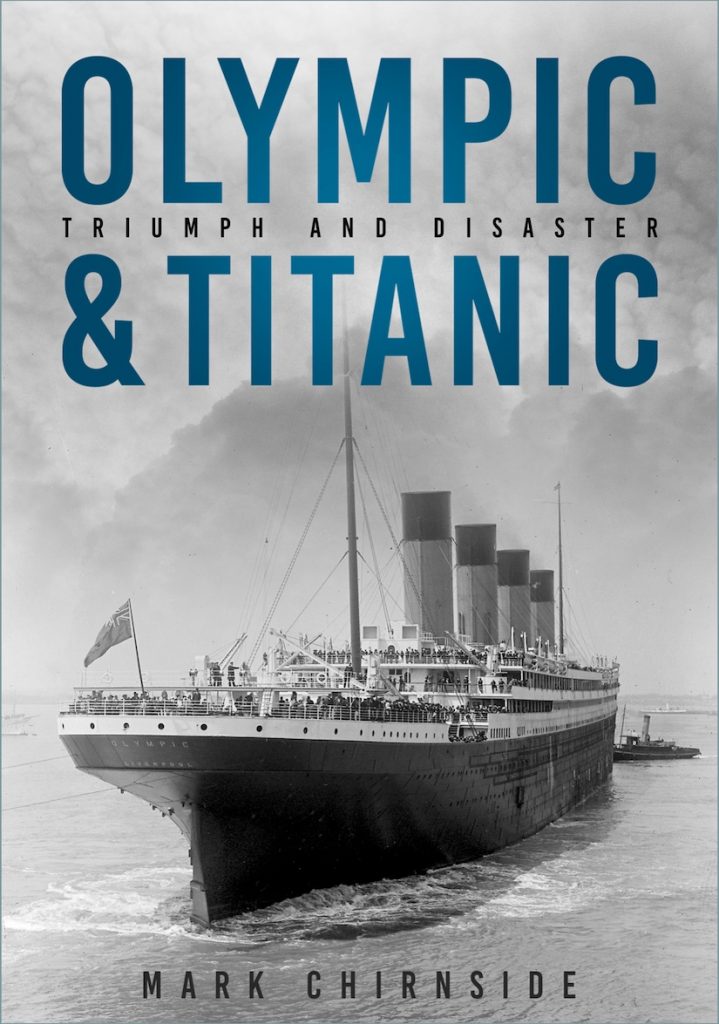

It was great to announce in September 2025 that the new book, Olympic & Titanic: Triumph and Disaster, will be published by the History Press in April 2026 (UK release). This book has been in the works for a long time but the completed manuscript was only submitted to the publisher at the start of May 2025.

It might be helpful to explain the process of taking a book from idea to reality.

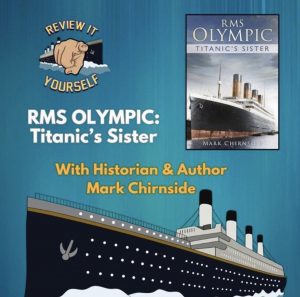

Authors are typically self employed and so each book project is written under its own contract and to a particular specification. The author and publisher will have already agreed a format (which might be a lavishly illustrated paperback book with fewer words or a large hardback book with a focus on the information in the text). Common practice is that there will be a range of tolerance for both the word count and the number of illustrations. For this book, the image count came in right in the middle of what had been agreed but the upper limit of the word count was 200,000 words. The finished manuscript ended up one word short!

The complexity of a project such as this is only appreciated fully by those directly involved. I was horrified to see I had burst through the maximum word limit and run to over 240,000 words. This entailed slashing the manuscript before it could even be submitted to the publisher. Cutting about 40,000 words required a disciplined editing effort on my part, but the end result was a sharpened focus on the key themes of the book. (To help visualise the extent of the cuts, these words are the equivalent of the Majestic book.) The cuts will not be wasted because they provide material for blog posts or articles in the future!

On submission of a book to the publisher, they will typically check over the manuscript and give it an initial read through to make sure that its content fits the original pitch. They will map out how it will all fit together in the finished product and how many pages will be required, taking into account the word count, number of images and intended use of those images. (As the author, I personally find it helpful to make recommendations concerning each image submitted. There might be some images which could be cut out if necessary, whereas another image might be rare or previously unpublished, meaning that it should be prioritised if space is at a premium during the book design process. In other cases, images are directly referenced in the main text itself so making sure that they are used in the final book is essential! The book designer will not necessarily be someone who knows the book’s subject and so it’s an important partnership between the author and designer to make sure we have a common understanding.) In the case of this book, although the word count was (just) within the upper limit and the image count was in the middle of the range, the page count rose from the projected 368 pages to 416 pages (plus the colour section). It’s a very big book!

Whipping the manuscript into shape typically involves a number of different editors. They might come back to the author with queries if they feel a certain statement is unclear, or where a section of a chapter might benefit from being restructured. In this case, I was relieved to hear that they thought the text was already in very good shape, but they made a number of recommendations which improved it a lot.

After months of work and queries back-and-forth, the author receives an initial set of page proofs to check over. This is where they see for the first time how the text and images have all been moulded together into the book design template by the design and editorial teams at the publisher. Proofreading is a mammoth task and usually involves multiple sets of page proofs. Initial comments / corrections are sent back to the publisher to be addressed; then a corrected set of page proofs is returned to the author to be checked and re-checked. It is amazing how many errors come to light only on the third read-through! A major challenge for the author is that they ‘know’ what they have written and so skim reading is not an option. It is a very tiring, focused process to try and read what is actually on the to-be-printed page rather than what the author thinks it says.

This book was researched and written over an extended period of time. One of my greatest pleasures was in learning new information about these ships from proof-reading my own book, because I ran across information again which I already knew but had slipped out of my memory! I benefited from the input of a number of colleagues who kindly reviewed sections of text pertinent to their particular expertise before the manuscript was submitted to the publisher. There were also others who were generous with their time and undertook pre-publication reviews based on the final product. Some of these reviewers came back to me with specific queries and in many instances I checked and re-checked the source material underpinning a particular statement. It goes without saying that any errors are the author’s ultimate responsibility.

Each book brings its own challenges. My own experience is that there will always be something that is missed (hopefully a very small detail such as a comma being used somewhere instead of a full-stop), which can be frustrating given how hard all the individuals have worked to try and eliminate that sort of error. Way back in 2006, when the first edition of the Majestic book was about to be signed off and sent to the printer, I realised to my horror that the page headers with the book title had ‘HMS’ Majestic rather than ‘RMS’. It was a last-minute correction that saved a considerable amount of embarrassment!

In this case, one of the illustrations provided by a photo archive was incorrect. The image (supplied directly to the publisher) showed the first class reading room rather than the first class smoke room. Although the archive reference number I had provided for the image was correct and I had fully intended to use a smoke room image, a well meaning individual at the archive had noticed that the archive catalogue description for that image incorrectly referred to the reading room and they substituted the image for the ‘correct’ one. This necessitated sourcing the image again – and explaining that the ‘incorrect’ image was the one required!

Formatting rules can create complexity. Should a particular word be in italics or not? It’s often the case that foreign language terms (such as the name of a dish on a French menu) will be italicised. However, each publisher will have their own ‘house’ style guide to ensure consistency between all of their titles. Some terms which are now in widespread use in English language publications are no longer appropriate for italics but should be formatted in roman. Changing the formatting from the original manuscript to the text in the book design template can introduce inconsistencies if one term is changed but another is missed. Therefore, it’s essential during the proofreading stage to make sure that all terms are formatted the same way. In the case of original source quotations where I have emphasised a particular point in italics, it is always necessary to make sure that a notation has been included to explain it is the author’s emphasis (rather than the original source document) and that the italics made it through to the final book.

Ship names represent a particular problem. By convention, they are always in italics but the formatting can be lost when the original manuscript is being transferred into the book design template. The most obvious ones are easy to spot but reviewing the entire text to make sure any ship names have not been missed is always a challenge – and there is always one which will be missed.

Indexing presents its own challenge. Indexing the content of the book can only be done very late in the process, because the layout needs to be 99 percent complete. We need to have confidence that any page numbers will not be changing after the material has been indexed. The process is laborious, but essential to help readers locate the material they want and to do justice to the sheer quantity of information in the book. A whole series of decisions need to be taken. Firstly, a judgement call on which subjects should be indexed. Titanic is an obvious example of a subject which should be included, but such a large entry necessitates numerous sub entries beneath the main topic. My approach was to cover the basic generalities first, then focus on areas where the book presents particularly important or new research and information. Then there are other issues to consider – should a person’s title be used, or just their surname and first name? What should be done in those instances where someone’s title changed? For example, William James Pirrie only became a Lord in 1906. He appears in the book decades before he had the title. Then there are ship’s officers. If an officer was promoted and appears in the text in both their junior and senior roles, which should be used? Arguably, their most senior role, but it does create its own complications. To keep things simple, I ended up using the simple surname, first name and/or initials for people’s index entries. All of this minutiae might not be apparent to someone who picks up the book and skims the index for topics.

Another last-minute job is checking all of the cross references (‘see page X’), where the main text itself refers the reader to another section that is relevant, or to an image. In some cases, image captions also refer the reader to the main text. Again, the final page numbers can only be confirmed once we’re confident nothing is going to be moved around or deleted for any reason. For the final sign off before the book goes to print, the author and publishing team have to be as confident as they can be that no significant errors have been missed.

After weeks of intense collaboration on the page proofs, sending masses of corrections / comments back and forth, it was great to go on leave for Christmas, set the out of office email and drink some mulled wine!

What’s planned for 2026?

There are more FAQs and other blog posts in the pipeline. (If you have any suggestions for particular topics, do get in touch. It might not be possible to respond to each individually, but all will be considered.) April is naturally a busy Titanic month and you will see lots of new posts reflecting that.

Announcements about the new book and ordering options will all be published on this website – if you have not yet subscribed for regular updates via this blog, be sure to do so in order that you won’t miss out!

Mark Chirnside’s eagerly anticipated new book, Olympic & Titanic: Triumph and Disaster, will be published by the History Press in April 2026!

This hardback volume, similar in scale to the acclaimed Titanic: The ‘Ship Magnificent’ books, will comprise of approximately 368 pages (including c. 160 black & white and c. 20 colour images). The text (200,000 words) is the result of years of research and the use of substantial primary source material. Needless to say, it contains a treasure trove of little known information and previously unpublished anecdotes. Whether your interest is in the design and engineering, financial, social or technical aspects of these ships’ history, you will learn something new.

Signed and personally inscribed copies will be available for purchase through this website and we will be sure to keep you updated over the coming months.

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same

Rudyard Kipling.

It is impossible to understand Titanic without appreciating the broader context: the development of the White Star Line and its competitors in the preceding decades; Anglo-German competition; the British fear of the ‘American peril’ as foreign capital increasingly controlled British shipping companies; and the relentless advance in shipbuilding and technology. This definitive reference volume explores the lead up to the construction of Olympic and Titanic; providing a step-by-step account of the design process; looking at the financial, logistical and political obstacles they had to tackle; the ups and downs of Olympic’s maiden season in 1911 and 1912; and summarising Titanic’s disastrous end. Relying on extensive primary source research and presenting much unpublished data, this new book is not only a valuable reference tool, but provides an essential insight into understanding this period of history.

For all the latest news, be sure to follow Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room through this blog and on social media!

In summer 2007, many sensationalist claims were made about the Titanic disaster. It is a topic which made headlines in 1912 and it remains newsworthy today. Editors know that the ship’s name will draw attention. Unfortunately, sensationalism is often what draws attention in the mass media. One example of this was a headline in a United Kingdom newspaper:

‘Titanic faced disaster from the moment it set sail, experts now believe…Even if the ocean liner had not struck an iceberg during its maiden voyage, structural weaknesses made it vulnerable to any stormy sea’. (Copping, Jasper. ‘Revealed: Titanic Was Doomed Before it Set Sail’, Daily Telegraph 10 June 2007)

The arguments in the media and on television included the claim that Titanic was not built to be strong enough for her intended service; that the enclosure of the fore end of the A-deck promenade was intended to strengthen the ship; and that the shipbuilders Harland & Wolff, at the behest of the White Star Line, had been forced to reduce the thickness of the hull plating to save money. None of these claims were based on evidence. (Why let the facts get in the way of a good story?)

All of these claims are addressed point by point in my article, Titanic: Allegations & Evidence, which was published back in 2015. (You can also listen to a detailed discussion of all these topics in the Steam & Splendor podcasts I participated in.)

A ship’s captain such as Captain Edward John (‘E.J.’) Smith was responsible for what was, ultimately, a floating town. Plenty of things could happen on a single voyage. One of many unusual incidents occurred about two years before the Titanic disaster. Early in 1910, the White Star liner Adriatic was leaving her New York pier when one of the ship’s stewards heard a revolver shot. One of the second class staterooms was found to be locked from the inside. The ship’s crew forced it open to find a passenger ‘lying on the deck with a bullet wound in the right temple’. Captain Smith wrote in the log:

The revolver was found lying close to the man’s right hand. The ship’s surgeon was called and pronounced life extinct.

Edward Ettridge, who had adopted the stage name ‘Ed Beppo’ for his English music hall performances, had shot himself in Alfred Burgess’ stateroom. He was, briefly and understandably, mistaken for Burgess. One of the ship’s officers had to call for a tug to take the body off the ship. Smith signed the entry in the ship’s log that Ettridge had died of a ‘bullet wound in right temple’, countersigned by Purser McElroy and Chief Surgeon William O’Loughlin. (The story is covered in ‘The “Big Four” of the White Star Fleet: Celtic, Cedric, Baltic & Adriatic’.)

On the same round voyage, which took Adriatic from Southampton to New York and back again, there were a number of crew who either deserted, ‘failed to join’ or ‘left by consent’ at Southampton. After the westbound crossing, Sixth Engineer Arthur Ward had to remain in New York due to ‘suspected appendicitis’. Then there was the case of a trimmer who had to be ‘fined five shillings for disobedience to lawful commands’. He admitted ‘refusing to obey orders, on the plea that the duty took him to the engine room, and that he signed articles to work in the stokehold only’. Another trimmer was reported ‘off duty owing to an injury to his right great toe, caused by a piece of coal falling on the foot’. And they had to take on additional victualling staff to make up for an unexpected number of extra passengers.

Two years later, Captain Smith, Purser McElroy and Chief Surgeon William O’Loughlin all perished in the Titanic disaster.

Above: Captain Edward John Smith (1850-1912). (L’Illustration, April 1912/Author’s collection)

My recent podcast with Titanrick for Curiositanic is now available (recorded in English with Italian subtitles). We discussed many topics related to the ship’s design and construction, debunking many inaccurate claims seen in modern day media reports.

Was Titanic poorly built and with substandards materials who contributed to the sinking? Let’s find out with one of the world’s leading experts on the Titanic.

No.

From 1907 to 1914, White Star’s Southampton to New York express service was operated by ships including Adriatic (1907-11), Majestic (1907-14), Oceanic (1907-14), Olympic (1911-14) and Teutonic (1907-11). The total number of third class passengers carried westbound was 116,491 whereas the total number of third class passengers carried eastbound was 110,211. (This data excludes commercial crossings made immediately after the outbreak of war in August 1914).

Total third class passenger numbers eastbound were actually higher than the westbound numbers in 1908, 1911, and the 1914 data up to August. The data for 1908 is the most dramatic example of this, with 10,121 third class passengers carried westbound and 24,282 eastbound. (Poor economic conditions in the United States led to a significant increase in eastbound passenger traffic.)

It is certainly true that many third class passengers travelled to the United States intending to start a new life there. Nonetheless the westbound and eastbound third class passenger traffic was much more balanced than many people seem to think.

(As an aside, the White Star Line had a good intermediate or secondary service from Liverpool provided by the ‘Big Four’. Their general manager, Harold Sanderson, thought that ‘the slower service…is the favourite service for the third class passenger’. He pointed out that the ticket costs ‘are slightly lower; they are lower than the Olympic’. The average third class passenger lists tended to be higher on the Liverpool to New York service, although that might also reflect that the ‘Big Four’ were newer and had superior third class accommodation to older ships such as Teutonic and Majestic.)

Above: Adriatic was the largest ship in the White Star fleet from 1907 to 1911. Although she was slightly faster and more luxurious than her three older sisters, the ‘Big Four’ were intended as intermediate ships. She was transferred to the Liverpool to New York service shortly after Olympic was completed in 1911. Another distinction is that the ‘Big Four’ had much greater third class passenger capacities than the company’s express liners. (Author’s collection)

No.

Contrary to popular belief, the enclosure of the fore part of Titanic‘s first class promenade on A-deck did not make any difference to her gross tonnage.

Titanic’s gross tonnage (not a measure of weight but, rather, the total enclosed space) was calculated as 46,328.57 tons. By comparison, Olympic’s gross tonnage was 45,323.82 tons when she was completed in 1911. Titanic’s gross tonnage was therefore 1,004.75 tons greater than her older sister’s. It placed her as the largest ship in the world.

It is a popular myth that the enclosure of part of the A-deck promenade was largely responsible for increasing Titanic’s gross tonnage. In fact, her registration certificate (completed in March 1912) specifically stated that the ‘open space on promenade deck, abreast windows port side – 198 feet long’ was ‘not included in the cubical contents forming the ship’s register tonnage’ (the same applied for the starboard side). (If it had been included in the gross tonnage calculation, it would have added 720.51 tons, increasing her gross tonnage to 47,049.08 tons.)

The real reason for Titanic’s increased gross tonnage was the expansion of the first class accommodation on B-deck at the expense of the original enclosed promenade, which accounted for the majority of the increase. This passenger accommodation counted as enclosed space, whereas the enclosed B-deck promenade on Olympic did not. Other changes, such as an enlarged officers’ quarters deckhouse, contributed to a much lesser extent as well.

In March 1913, Olympic’s own gross tonnage increased to 46,358.70 tons, following a major refit which included expanding the restaurant and adding a Café Parisien on the starboard side of B-deck. These modifications ensured that the remainder of the enclosed promenade space on this deck was now counted as enclosed space in the gross tonnage calculation. She emerged from the refit with a higher gross tonnage than Titanic, even though her A-deck promenade was never enclosed.

It is common to hear comments about the lifeboat regulations in force at the time of the Titanic disaster, which linked lifeboat provision to the size of the ship. Famously, the rules had come into force in 1894 when the largest liners afloat were Cunard’s Campania and Lucania. They provided for a scale of ship size based on gross registered tonnage and the largest category was ships of 10,000 gross tons and above. By 1901, the largest ship afloat was double that; by 1912, Titanic was more than four times that.

However, it’s often overlooked that a ship’s gross tonnage was not necessarily the best guide to how many passengers and crew she would carry. We can see an example of this in comparing Cunard’s Carpathia with Olympic as at April 1912. The number of passengers and crew capacity did not correlate to the fact that Olympic was three times Carpathia’s size. The reason for this is that the Cunard ship carried so many third class or steerage passengers, who were allocated significantly less space per person.

Above: One of many slides from my September 2021 presentation at PRONI, Olympic & Titanic: ‘A Very Remote Contingency’ – Lifeboats for All. (Author’s collection)

A question came up a while ago in an online discussion forum concerning the construction of the three ‘Olympic’ class ships. The poster asked: ‘I mainly want to know if one was built a little stronger than the other’. The issue of strength is a complex one. However, my answer to that is that all three ships were built to the same standard of strength. I’ll explain an example of that standard.

William David Archer, who was the Principal Ship Surveyor to the Board of Trade (since 1898), explained how a key measure of strength was calculated, to take into account the ship’s structure [scantlings], length, weight [displacement] and tendency to bend:

24323. How do you test your standard of strength – how do you arrive at your standard of strength apart from the question of scantlings?

– We do this. We get from the builders the drawings of the vessel. One of these drawings is a midship section. That midship section is a section as if you cut the ship right through the middle. It shows the thickness of all the plates, the longitudinal members of the ship – for example, the thickness and width of all the plates forming the skin of the ship and the deck of the ship.

24324. But those are the scantlings, are they not?

– Those are the scantlings of the ship. We then make an estimate of what the stress on the gunwale of that ship in tons per square inch will be, on the assumption that the vessel is subjected to a bending moment equal to the whole displacement of the ship, in this case about 52,000 tons multiplied by one -thirtieth of the vessel’s length. In that way we get at a certain figure of so many tons per square inch on the shear strake [hull plating at the side of C-deck].

In the case of Olympic and Titanic, that estimate of stress came to 9.89 tons per square inch. This is very much in line with the standard shipbuilders of the period worked to for mild steel ships, which was to work to about 10 tons or less. On this measure, they were about the same or stronger than all the other large liners of the period that I have data for, excepting Oceanic and Aquitania. The figure may have differed slightly for Britannic, because she was a little wider and had a correspondingly greater weight (displacement) of about 1.6 per cent, which would have increased her bending moment.

We know from the Olympic/Titanic and Britannic midship section plans that the fundamental structural details of all three ships (including the keel, double bottom, hull plating, hull frames, columns, pillars, deck beams, etc.) were all the same. The scantlings (dimensions and thicknesses of these key structural components) were the same. There should be nothing surprising about this. Although we hear so much about the substantially greater size of these ships measured by gross tonnage, in terms of displacement they were ‘only’ about 27 percent heavier than ships such as Adriatic. Harland & Wolff had a lot of practical experience as well as theoretical design principles to determine the structural design requirements. By way of some benchmark comparisons, it is telling that these ships’ scantlings are very similar to other large liners of the period such as Lusitania (1907), Aquitania (1914), Imperator/Berengaria (1913). They are also comparable to Queen Mary (1936).

Harland & Wolff were also familiar with the standards of Lloyd’s classification society. Naval architect Edward Wilding said that ‘about one-third to one-half’ of the ships Harland & Wolff built were classed by Lloyds. He was questioned about Lloyds requirements as well as Olympic’s construction (both as built in 1911 and following the modifications to improve her watertight subdivision in 1912-13) when he testified for the Limitation of Liability hearings in May 1915:

Q. When you have mentioned the construction of the Olympic, have you referred to the original construction of the Olympic or the construction as she is today?

– The construction is generally the same, as structurally we have made very little change.

He went on to say:

Q. Do you mean to say that from your knowledge of the customs at Lloyds the Titanic would have been passed at Lloyds without any change whatever?

– I can’t put it any higher than this: I believe if we were to offer the Olympic today to Lloyds they would class her without making any further requirement. I have no authority for it, though.Q. That is, the Olympic in her present condition?

– Or as she was finished originally. We have made no change that would affect Lloyds classification; none of the changes made would have affected Lloyds’ views as to classing her.

Wilding stated that Harland & Wolff had to do fewer repairs to Olympic than any other large ship they had built. Their experience operating Olympic in both summer and winter conditions up to early 1912 led them to make only minor modifications, including to the foremost hatch design and its cover. The result was that, when ‘Yard Number 433’ (Britannic) was ordered in 1911, her structural design and scantlings were a duplicate of Olympic/Titanic in all major respects.

When, following the Titanic disaster, White Star specified that Olympic and Britannic needed to be modified to float with an unprecedented number of watertight compartments flooded, the only reason that some of the watertight bulkheads (and the watertight doors in them) were strengthened was because those particular watertight bulkheads were being extended so much higher. The original watertight bulkheads were already built to a very high standard of strength. The plating and stiffening were both well in excess of Lloyd’s requirements which post-dated the Titanic disaster and the Board of Trade had noted the strength of the bulkheads throughout was ‘very ample’, after doing a detailed comparison between the structural design compared to what the regulations required. Edward Wilding noted that a head of water ‘about 150 feet’ deep from the bottom of the watertight bulkheads would have been needed to break the lower part of them, which was many times higher than the head of water they would ever have been called upon to hold back. Nonetheless, to ensure a good margin of safety the watertight bulkheads which were raised were also strengthened further.

We know Cunard changed aspects of Aquitania‘s design to bring her closer into line with Olympic after their naval architect, Leonard Peskett, examined her in 1911. In 1925, the Board of Trade’s Chief Ship Surveyor used comparative data from Olympic as a benchmark example of a strong ship, as did a professional from the consultant naval architectural firm Roscoe & Little, based in Liverpool. Roscoe & Little were doing an analysis of options for different schemes of repair to the White Star liner Majestic (originally HAPAG’s Bismarck, launched in 1914), which had suffered a significant structural failure in stormy seas during December 1924. Those schemes ranged from a minimalist one restoring Majestic to her strength as originally completed in 1922, to a much more substantial proposal which would significantly increase her strength. (Roscoe & Little noted that under the minimalist scheme of repair, they estimated that Majestic would be about 20 percent weaker than Olympic.) These examples help illustrate the context in which shipbuilding professionals viewed Olympic at the time.

There seem to be many people who think Titanic was a ‘weak’ ship, given that she broke up in the final stage of sinking. In reality, her stern was lifted out of the water for an extended period, subjecting her to stresses a multiple of what she would have experienced in the worst North Atlantic storm. Any structure will fail if it is subjected to stresses far beyond what it was designed for. That hasn’t stopped all too many conspiracy theorists taking key details out of context in recent years.

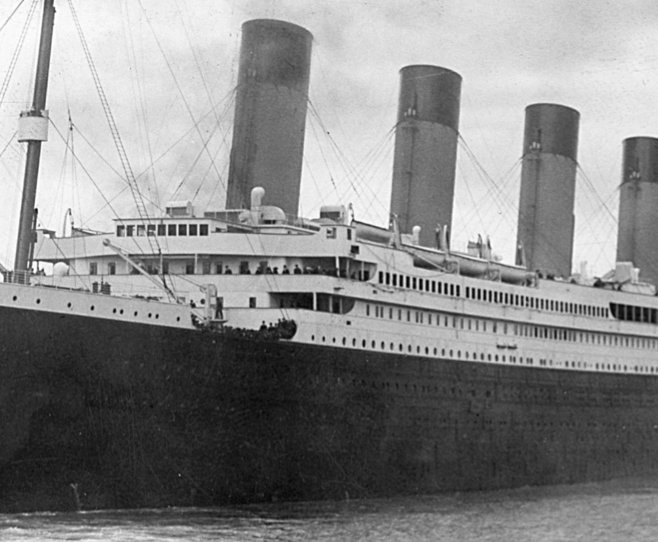

Above: Olympic as built, 1911. Eight of the fifteen watertight bulkheads extended up to D-deck and the remainder to E-deck. Her watertight subdivision was designed on the basis that she needed to float with any two compartments flooded, but Harland & Wolff built in such a margin of safety that she was largely a three-compartment ship. She would also float in a number of scenarios with four compartments flooded. (The Shipbuilder, 1911/Bruce Beveridge collection – modified to show the outline of watertight bulkheads)

No.

While nobody has been able to confirm for definite what did happen to the Titanic lifeboats which were recovered and taken to New York, we know that they did not end up being reused on Olympic.

Olympic received a number of temporary collapsible lifeboats in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, in April 1912. She completed her final round trip of the year between Southampton and New York in October 1912. At that time, Titanic‘s lifeboats were still in New York.

The reason that Olympic was withdrawn from service in October 1912 was so that she could return to Harland & Wolff’s Belfast shipyard for a major refit. This included a more permanent solution to her lifeboat apparatus, replacing the collapsibles which had only been intended as a stop-gap solution.

Above: Harland & Wolff blueprint reproduced in Olympic Titanic & Britannic: An Illustrated History of the ‘Olympic’ Class Ships (recommended further reading: below).

In February 1913, Harland & Wolff submitted a blueprint to the British Board of Trade confirming the new lifeboat arrangements and the additional davits which had been fitted to handle them. The Board of Trade had to give approval to permit the ship to go to sea with passengers and this submission was a key part of that process.

They included a ‘Summary of Boats’:

| Description | No. of Persons | Total No. of Persons | |

| 14 Open Lifeboats 30 x 9 x 4 | 64 | 896 | Boats Originally Fitted to Comply with Old B/T Regulations |

| 2 Wood Cutters 25 x 7 x 3 | 33 | 66 | |

| 4 Decked Lifeboats 28 x 8 x 3-8″ | 40 | 160 | |

| 12 Open Lifeboats 27-5″ x 8-6″ x 3-7″ | 50 | 600 | New Boats to Comply with new Board of Trade Regulations |

| 12 Decked Lifeboats 27-5″ x 8-6″ x 3-7″ | 46 | 552 | |

| 8 Open Lifeboats 29 x 8-6″ x 3-7″ | 53 | 424 | |

| 14 Decked Lifeboats 30 x 9 x 3-7″ | 52 | 728 | |

| 2 Decked Lifeboats 28 x 8 x 3 | 42 | 84 | |

| Total Number of Persons Boats Will Accommodate | 3510 | Total 68 Lifeboats | |

| Total Number of Persons on Board | 3450 | ||

| Spare | 65 | ||

Above: Olympic Lifeboat Configuration, February 1913. The ‘Description’ includes the number of each type of boat and then the boat dimensions (length x breadth x depth) in feet (rounded) and -inches (“) as applicable. Lifeboat capacities sometimes differ in different source material, depending on the method of calculation and whether capacities have been rounded up or down. The ‘Boats Originally Fitted…’ are Olympic‘s original lifeboats, which were identical to Titanic’s. (They illustrate this point well, because the capacities shown for the original 20 boats come to 1,122 persons whereas the usual figure is 1,178. See: Titanic: The Ship Magnificent [History Press; 2016] for further details on how lifeboat capacities could be calculated, including Stirling’s Rule.) The ‘New Boats…’ are those fitted in 1913.

All of the new, additional lifeboats were different in size and carrying capacity to Titanic’s lifeboats. Some of the new boats were also delivered late. On 11 March 1913 Harland & Wolff informed the Board of Trade that they would retain ten Berthon and six Henderson collapsibles on board as a temporary solution, while ‘doing all possible to expedite the delivery of the remaining sixteen decked lifeboats’ that would be ‘placed onboard at the earliest possible opportunity’. The orders placed and the delay in constructing or delivering these sixteen boats once again demonstrate that they were newly built.

This article represents an expanded version of material published by Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room in July 2005. It is published with revisions (up to July 2025).

There were reportedly three sets of copies of Andrews’ notes taken on Olympic’s maiden voyage – a copy for the White Star Line, a copy for Harland & Wolff, and his personal copy. Some of the notes he took have been summarised before (see: Lepien, Ray. ‘Olympic The Maiden Voyage’. Titanic Commutator 2003; Volume 27 Number 162; and: Marre, Jean-Philippe. Thomas Andrews: Architecte du Titanic. Lulu; 2015.) I was fortunate to purchase some of Andrews’ notes in summer 2004. I then published extracts online in July 2005 and again as an appendix in the revised and expanded edition of The ‘Olympic’ Class Ships: Olympic, Titanic & Britannic (History Press; May 2011), however many of Andrews’ recommendations were missing. At that time, I did not realise quite how many were unavailable but, over the years, a number of researchers have kindly shared material and helped to fill in the gaps.

We know that the set is still not complete because Andrews numbered his notes consecutively, from 1 to 56. Work is ongoing to try and reassemble the entirety of what he wrote, however notes 28 to 39 and 47 to 55 inclusive are still missing (as of July 2025). This revised article adds to the notes published previously.

I am grateful to researchers including Scott Andrews, Bruce Beveridge, Robin Beuting, Gunter Babler, Mark Evans, Joao Goncalves, Ray Lepien and Bill Sauder, for sharing information and supporting with my interpretation of either the handwriting or a particular detail. Any errors are mine alone.

It’s widely believed that construction of the three ‘Olympic‘ class ships was made possible by the use of American money – resources from either J. P. Morgan or IMM. The truth is the opposite: White Star was not supported by IMM’s resources. IMM was supported by White Star. Construction was financed through capital raised in the United Kingdom. This article (external link) explains in detail how:

It was first published in the Titanic International Society’s Voyage July 2020: Pages 135-39.

The subject of how the construction of the ‘Olympic‘ class ships was financed is a good case study showing the necessity of using primary sources (original documentation) rather than secondary sources (such as books or television programmes). We have the prospectus which was issued to investors in 1908, in which the White Star Line explicitly stated why they were borrowing the money; we have the IMM annual report from the same year, which carried a statement on behalf of President J. Bruce Ismay and the Board of Directors, explaining that the White Star Line was borrowing the money and giving their reasoning for doing so; and we have records from both the financial press and the London Stock Exchange Daily Official Lists (SEDOL) confirming that the bonds were issued and the prices they traded at when they changed hands on the market. In contrast to this, many modern books or television programmes have simply claimed that J. P. Morgan or IMM’s capital resources were made available to finance construction: this inaccurate assumption is simply false.

Above: ‘Movements in Shipping Securities’ reported on 18 June 1914. They were listed in alphabetical order by the name of the shipping line, so the many rows after ‘Cunard’ and up to ‘O’ have been deleted; ‘Oceanic Steam. Nav.’ is an abbreviation for the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, which was the legal name of the White Star Line. ‘Deb’ denotes that the security being traded was a debenture bond rather than a stock. (Shipbuilding & Shipping Record, 1914/Author’s collection)

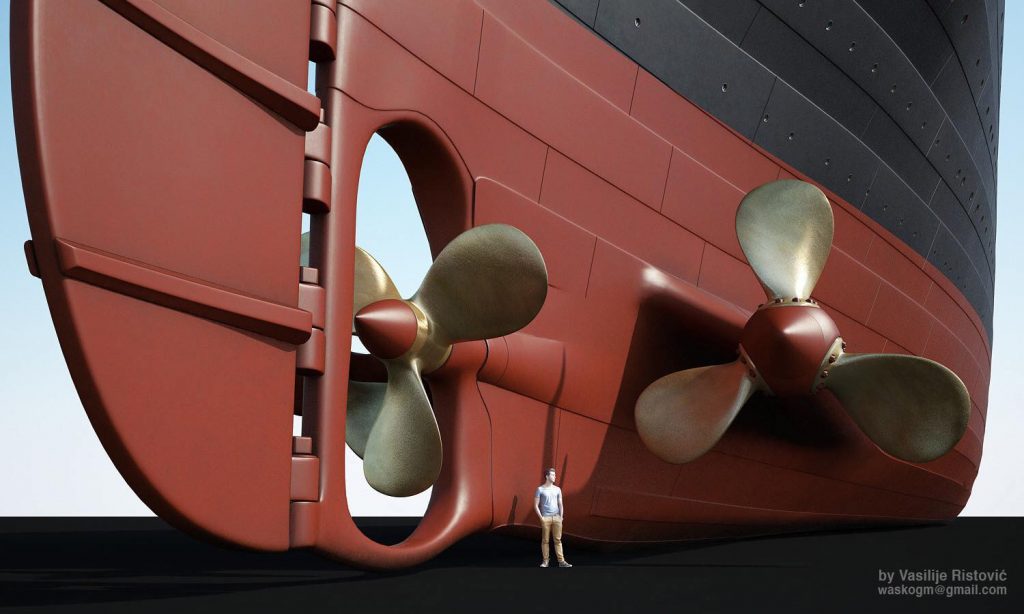

For decades, it was simply assumed that Titanic‘s propeller configuration was the same as her sister Olympic‘s. This assumption became accepted as fact. All too often, photos of Olympic‘s propellers were used to stand in for Titanic without the descriptions making clear that they were photos of her older sister ship. (There are no known photos of Titanic in dry dock with her propellers fitted and visible.)

However, in 2007 I was researching the Harland & Wolff records (supported by a local researcher, Jennifer Irwin). This material had been deposited with Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI) between 1972 and 1994. It included documentation colloquially referred to as the ‘Harland & Wolff order book’, which kept a record of the key dates for each ship such as the contract date, when the shipyard and engine works were ordered to proceed, when the keel was laid, when the double bottom was completed, when the hull was fully framed, when the ship was launched and delivered. The ship’s basic dimensions and propelling machinery details were also recorded.

Of particular interest to ‘rivet counters’ or technical researchers was a series of five volumes of engineering notebooks, which focused on the technical aspects of the hundreds of ships they completed, as built: these included each ship’s size, displacement and propelling machinery particulars in great detail (such as the size of engine components, the boiler specifications and propeller specifications). The details were recorded meticulously. It is not clear exactly when they were transferred from Harland & Wolff, but the best guess is that this was probably the early 1970s. These records were also classified as closed, subject to researchers making a specific application to review them, which stands in contrast to other archival records that are classified as open (without such access restrictions).

The entries for Titanic state that her propeller configuration had an increased pitch of the port and starboard propeller blades (compared with the 1911 Olympic configurations) and a slightly larger centre propeller which had three blades instead of four. In other words, contrary to the assumption that Titanic‘s propeller configuration was closest to Olympic as she was in 1911, it was closer visually to Olympic‘s configuration after her 1912-13 refit. In hindsight, there should be nothing surprising about this. Shipbuilders of the period were constantly tweaking and experimenting with the optimum propeller designs and we know from J. Bruce Ismay’s testimony that Harland & Wolff had advised him they expected Titanic to be slightly faster than Olympic.

This material from Harland & Wolff is a primary source, which is far superior to secondary source material. As explained in the Harvard Library’s Research Guide for the History of Science:

Primary sources provide first-hand testimony or direct evidence concerning a topic under investigation. They are created by witnesses or recorders who experienced the events or conditions being documented.

Secondary sources were created by someone who did not experience first-hand or participate in the events or conditions you’re researching.

The key distinction here is that, whereas many secondary sources simply repeated an assumption about Titanic‘s propellers that was made by people who were not there in 1912, the primary source material was produced first hand by personnel at Harland & Wolff who were tasked with keeping a record of each completed ship’s technical particulars. It is the contemporary record which was kept by the shipbuilding firm who completed Titanic in 1912.

This dossier groups together the primary source evidence and analysis of that material, including the Harland & Wolff evidence published in 2008 and other supporting evidence discovered by other researchers in the years since.

Sadly, Titanic’s propeller configuration has been the subject of ill-tempered and vitriolic arguments online. What was simply an interesting discovery of a previously unknown difference between her and her older sister ship has become the topic of frequent hysteria. Nonetheless, despite all these arguments, there is no debate as far as the primary source evidence is concerned. From the historian’s perspective, what counts is that our interpretation is based on the best available evidence. The best information we have about Titanic’s propeller configuration (to date) is Harland & Wolff’s own records.

Above: A stunning illustration of how Titanic‘s propellers most likely appeared, based on the propeller specifications recorded by Harland & Wolff. (Courtesy Vasilije Ristovic, 2019)

The On A Sea of Glass and Part-Time Explorer 113th Anniversary Titanic Livestream, which was broadcast on Thomas Lynskey’s Part-Time Explorer channel on YouTube, is available to replay.

Titanic was headline news for weeks following the disaster. On 16 April 1912, the New York Times included an article about Captain Smith and his career in their coverage. Within that article were extracts from comments Smith had reportedly made on the conclusion of Adriatic‘s successful maiden voyage almost five years earlier, to the press in New York. It is easy to see why a newspaper reporter would want to quote Smith’s comments. He had spoken about his ‘uneventful’ career and the love of the ocean that he had had since childhood. Then, he went on to talk about the safety of modern passenger liners. Those comments had a sad irony given the recent disaster. One common quotation, used by historians in the decades to come, was:

I will say that I cannot imagine any condition which could cause a ship to founder. I cannot conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.

Back in 2008, I began to worry that I had not been able to find Smith’s comments in newspaper coverage from that summer of 1907. I found it somewhat uncomfortable that our source seemed to be only a post-disaster publication. However, thanks to the effort of a number of researchers including the late Mark Baber, Smith biographer Gary Cooper, and Dr. Paul Lee, sources for the quotation were found from pre-disaster publications. These included press reports dating from later in 1907 through to a report in The World’s Work in April 1909 (shown in an extract from a slide in my presentation to the British Titanic Society in April 2024, below).

By comparison, the New York Times’ report published on 16 April 1912 had some interesting differences in emphasis. For example, rather than saying ‘modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that’, the pre-disaster quote was ‘modern shipbuilding has reduced that danger to a minimum’. The New York Times also summarised Smith’s preceding comments, paraphrasing him: ‘Captain Smith maintained that shipbuilding was such a perfect art nowadays that absolute disaster, involving the passengers on a great modern liner, was quite unthinkable. Whatever happened, he contended, there would be time before the vessel sank to save the lives of every person on board’. The paraphrased summary was broadly accurate, but it omitted the comment ‘I will not assert that she is unsinkable’ [emphasized above].

All of Smith’s reported comments are important and they need to be understood in their full context. It’s also important to recognise that even the pre-disaster quotations are from a secondary source and rely on a degree of assumption that what Smith said was reported with reasonable accuracy!

I am honoured to have been invited to participate in the On A Sea of Glass and Part-Time Explorer 113th Anniversary Titanic Livestream, which will be broadcast on Thomas Lynskey’s Part-Time Explorer channel on YouTube. It starts at 9.30 p.m. Eastern Time (United States) on Monday 14 April 2025 / 2.30 a.m. (United Kingdom) on Monday 15 April 2025. The livestream will also be recorded and available to replay afterwards.

Hosted by Thomas Lynskey, it includes special guests Alex Moeller and Levi Rourke; historians and On A Sea of Glass co-authors Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton and Bill Wormstedt; and guest historians Don Lynch, Ken Marschall and I.

Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room first came online back on 1 April 2005! Since then, it has expanded substantially and been redesigned twice (2007 and 2022) to keep it fit for purpose. The nature of the internet and online content means that so many websites which were available then are no longer with us. One of those websites was the Titanic Research & Modelling Association (TRMA) which was pioneering in its day. (Fortunately, much of it is archived and preserved as a static site.)

My article ‘Olympic & Titanic: Refining a Design‘, is a revised and expanded version of a short article of mine published by TRMA in 2005. It was published in the British Titanic Society’s Atlantic Daily Bulletin 2019: Pages 18-22.

Author’s Note: Back in 2005, I published information about some previously unknown refinements to Titanic based on experience Harland & Wolff gained from observing Olympic during a particularly severe North Atlantic storm in January 1912. The article was published on the Titanic Research & Modelling Association (TRMA) website. It discussed some modifications to some of her rivetted joints fore and aft: Olympic’s great length meant that the stresses at these points – from about a quarter of her length ahead of the stern and a quarter of her length abaft the bow – required some additional reinforcement, beyond what previous experience had suggested was necessary, to prevent rivets in these areas becoming gradually slack in severe weather conditions.

It goes to show how much we are still learning about the ‘Olympic’ class ships all these years later, but the demise of the TRMA website offered an opportunity to publish this new article. It contains the original article’s information about the changes to Titanic, supplemented by additional material, including new diagrams of both Titanic and Britannic, and contextual information about other large liners of the period.

When I published this information for the first time all those years ago, my view was that these refinements demonstrated the fundamental strength of Olympic. Harland & Wolff were following their usual practice, as Edward Harland had explained back in 1873, of using their experience from operating new ships over their early voyages to proactively make improvements to them and their sister ships. She experienced a storm in January 1912 which was one of the worst of her entire career and which Captain Smith reportedly said was the worst he had ever seen in all his decades of North Atlantic service. The North Atlantic in winter storm conditions is an extremely hostile environment but she came through it: the modifications were not intended to remedy any serious defect which had occurred but to prevent future maintenance requirements. Ships such as Olympic were built as fast passenger and mail steamers, designed to run through these hostile conditions even at relatively high speed.

Nonetheless, I was contacted shortly after the original article’s publication by an American conspiracy theorist who was trying to argue that Titanic was a weak ship that sank because she broke up, rather than the reality that she was a strong ship which broke up in the final stages of sinking. (The cause of the breakup is that she was exposed to stresses over a prolonged period that were far greater than what she would have experienced in the worst possible storm conditions that she was designed for. No comparable passenger liner was designed to have her stern raised clear of the water for an extended period, unsupported.) He sought to use the information I had published (which he mischaracterised and deliberately took out of context) to support his claims and, unfortunately, all too many others followed suit: It is a very common problem with Titanic that many people look at her in isolation without looking at the broader context or doing an objective analysis. That context includes her sister ships as well as other large liners of the period.

Sensationalism is often what draws attention in the mass media and one example of this was a headline in a United Kingdom newspaper, which echoed his claims:

‘Titanic faced disaster from the moment it set sail, experts now believe…Even if the ocean liner had not struck an iceberg during its maiden voyage, structural weaknesses made it vulnerable to any stormy sea’. (Copping, Jasper. ‘Revealed: Titanic Was Doomed Before it Set Sail’, Daily Telegraph 10 June 2007)

This headline stands in stark contrast to the assessments of experienced professionals at the time, summarised by two short quotes from a number of examples. Edward Wilding, Harland & Wolff naval architect, 1915:

We have had less repairs to the Olympic than to any large ship we have ever built, due to external causes, of course’

Principal Ship Surveyor to the Board of Trade, 1925:

Olympic…has, I think, proved to be a successful ship in the matter of strength’.

On the positive side, the design changes outlined in my article have also been analysed and cited by serious researchers. (For an analysis of these changes and their potential impact on Titanic, see Parks Stephenson’s article ‘What Caused Titanic to Sink?’ in the Titanic Historical Society’s Titanic Commutator 2014: Volume 39 Number 206. Pages 92- 100. See, also: Rudi Newman’s ‘A “Riveting” Article – an Historical Rejoinder to Metallurgical Studies of the Titanic Disaster’ in the British Titanic Society’s Atlantic Daily Bulletin 2012: Pages 18-30.) Following on from my 2005 article, when The ‘Olympic’ Class Ships: Olympic, Titanic & Britannic was published (History Press; revised and expanded edition, 2011) I included this information on page 226.

I have to say that it’s the best Titanic related media I’ve ever heard or seen…your contribution to dispelling the myths is just outstanding. Compelling and fascinating.

All too often, sensationalist claims are made in the media about Titanic and the disaster which befell her. A typical theme is claims of an ‘Achilles Heel’, design ‘flaws’, poor materials or even that Titanic was doomed from the start. The mundane reality that Titanic was a well built and designed ship, which sank because she sustained extraordinary damage as a result of an awesome encounter with an iceberg, does not make headlines.

I was pleased to participate in two podcast episodes where we discussed a large number of these issues over the course of nearly two hours. We covered a great deal of material. Grab a coffee and listen in!

Part 1: Hosts Tad Fitch and J. Kent Layton are joined by author and researcher Mark Chirnside for an eye-opening discussion that challenges everything you thought you knew about the Titanic and her sister ships. Over the years, myths have surfaced claiming these iconic liners were poorly designed, made with subpar materials, and doomed from the start. But how much of that is actually true? Join us as we discuss the allegations, break down what the actual historical documentation and context indicates, and dispel some long-held myths.

Part 2: Join hosts Tad Fitch and J. Kent Layton as they continue their discussion with researcher Mark Chirnside, diving into the historical record to uncover the truth about the safety, reliability, and durability of the Titanic and ‘Olympic’ Class ships. How well-designed and safe was RMS Olympic—both before and after its post-Titanic disaster refit? Tune in as they examine the evidence, compare the design of these ships to their contemporaries and debunk long-held myths.

A new article of mine, ‘A Voyage on Olympic: Willem Frederik Piek Jr.’s Notes for the Holland America Line, December 1911′ (external link) has been published on Encyclopedia Titanica.

Born in Amsterdam on 16 March 1874, Willem Frederik Piek Jr. became the head agent of the Holland America Line in New York, in 1912; four years later, he became a director of the company, serving in that position until 1935. In December 1911, he boarded Olympic at New York for an eastbound crossing (the passenger list also included ‘Mrs Piek’). Travelling first class, his objective was to check out what life was like onboard. How comfortable was her passenger accommodation? How was the White Star service? How might they lure away her passengers?

His meticulous notes, handwritten in Dutch, provide fascinating details of what it was like to sail on Olympic. They contain the sort of observations that cannot be found in period journals such as The Shipbuilder, or in chatty, casual letters home from passengers. It all adds to the social history of Olympic and provides a glimpse of what life might have been like onboard Titanic, such as first class passengers stealing spoons from adjacent tables, or maids and valets hanging around the companionways because they only had a dining saloon on C-deck.

One common factor when observers acting for one shipping line wrote about competitors’ vessels is that they often seemed very critical about particular aspects of a ship. This can also be seen in reports Cunard’s naval architect, Leonard Peskett, wrote about Olympic in August 1911 and Imperator in June 1913. If advertisements of the period extolled a ship’s virtues, then competitors’ criticisms provide a counterweight. The reality lies in between. Indeed, we also see positives such as the lack of items which rattled in first class staterooms.

This is believed to be the first time that his notes have been published. They illustrate the importance of diversifying beyond English language sources. His observations and a vast array of other hitherto unpublished material will be included in Mark Chirnside’s next book, from which much of this article is drawn from.

This article was first published in the Titanic International Society’s Voyage 128 July 2024: Pages 158-62. (A German language version was published in the Swiss Titanic Society’s Titanic Post 129 September 2024: Pages 125-30.)

A number of the locations that Piek referred to in his notes, such as the maids’ and valets’ dining saloon, can be seen recreated as they were on Titanic through Titanic: Honor & Glory’s DEMO 401 Update 2.0 Release Day Tour.

Above: The Holland America liner Rotterdam (1908) was built by Harland & Wolff. She introduced many innovations and set a number of new standards in passenger accommodation. (Author’s collection)

My recent podcast with James Penca for his Titanic Witnesses series is available. We discussed my personal research journey, from when I first started visiting archives and undertaking research using the primary source materials, to common problems with Titanic information disseminated in the media and secondary sources. There are a large number of aspects of Titanic‘s history where there is widespread inaccurate information in secondary sources (such as media reports or television programmes), which is often subject to fierce debate online as to what is correct or not. The use of primary sources is essential to forming the most accurate understanding of history that we can. In many cases, the primary sources provide a definitive answer. Much of the confusion we see could easily be avoided by relying on the primary documentation, but instead we see demonstrably false statements repeated from one secondary source to another.

Have you ever wondered how much work goes into the writing of your favorite history books? This week, we are joined by celebrated maritime author Mark Chirnside for a look at the many road blocks and pitfalls that come with Titanic research. Welcome to WITNESS TITANIC, a podcast where we interview witnesses of the infamous Titanic disaster including modern experts, enthusiasts, and even the survivors of the sinking. Like the century-old inquiries that came before us, we may never fully determine what really happened on that cold April night but you may be surprised to find how close our efforts will bring us to Titanic herself…

It was an honour to participate as a special guest in an episode of Joanna Strassburg‘s RMS Titanic Reflections: Deep Conversations.

We had a wide-ranging three hour discussion concerning all manner of Titanic and White Star Line related subjects. I spoke a lot about my various research projects and the many different books I’ve authored or co-authored over the years.

Click here or on the image below to watch a replay of the livestream on the RMS Titanic Reflections Facebook page!

Please join us for this very special LIVE event on Monday, September 2, 2024. Mark Chirnside will be the special guest for Deep Conversations Episode 18. Mark is a talented and very knowledgable author and historian. He has appeared in many documentaries to provide his expertise regarding many topics….

Gross tonnage is NOT a measure of weight

There is a lot of confusion about the subject of Titanic‘s weight, which is not helped by some of the terminology used. We often see references to the ship’s ‘gross tonnage’. However, despite what the term implies with the use of the word ‘tonnage’, it is not a measure of weight. It actually measures the total enclosed space within the ship’s hull and superstructure. Therefore references in the media which refer to a comparison of ‘gross tonnage’ and to Titanic being approximately 1,000 tons ‘heavier’ than her sister Olympic are completely inaccurate (and all too common).

The total weight of the ship (displacement) was calculated as 52,310 tons when she was loaded to her designed draught of 34 feet 7 inches – precisely the same as her sister Olympic. (Their larger, younger sister ship Britannic had a displacement of 53,170 tons and the same designed draught.) This was made up of the lightweight (the weight of the ship herself, including her hull, engines, machinery and permanent fittings before she was loaded for sea) plus the deadweight (the weight of the cargo loaded onboard, including everything from her human cargo – passengers and crew – to the coal, other supplies for the voyage and commercial cargo carried in the ship’s holds). These figures are all given in the British, Imperial measure.

This data is taken from shipbuilder Harland & Wolff’s records and summarised below. We see that Titanic in an unloaded condition weighed 480 tons more than her older sister Olympic and that her deadweight was correspondingly smaller. However, both ships’ total weight (displacement) was the same assuming that they were loaded to their designed draught.

It is important to understand that, despite all the confusion in secondary sources (such as articles, books, television programmes and so forth), the primary source evidence (original, contemporary documentation) is all very clear in regard to how much the ship weighed. The ship’s displacement is confirmed in multiple original documents, including Harland & Wolff’s records; Olympic‘s displacement scale (which shows how much water she displaced at a given draught); and the Board of Trade. It is benchmarked against figures Thomas Andrews provided for Olympic in 1911.

No.

The available evidence indicates that Harland & Wolff used three spare blades as replacements for the three damaged blades on Olympic’s starboard propeller.

George Cuming, one of Harland & Wolff’s managing directors, was one of a number of professionals to see Olympic in drydock. On 14 October 1911, he summarised the necessary repair work to an Engineer Commander, whose report went to the Director of Dockyards (on behalf of the Admiralty) some days later.

Olympic’s Starboard Propeller Blades

There was some good news: ‘There are no marks on the propeller blades of the centre and port shafts to show that these have been touched by anything at the time of collision’. Unfortunately, the starboard propeller blades were all damaged:

The three blades have been removed; they are damaged towards the tips. They are probably bent as well although this is not obvious. Mr. Cummings’ [sic] proposal is to scrap these three blades, appropriate three spare and replace the spare blades used. The blades are…manganese bronze.

Olympic’s Starboard Propeller Boss

The starboard propeller boss itself (the cylinder at the centre of the propeller to which the blades were attached) was ‘apparently undamaged’ but either of Titanic’s port or starboard propeller bosses were available to use as a replacement in the event that any damage to Olympic’s starboard propeller boss became apparent later. (There is no evidence that it did.) Harland & Wolff proposed to ‘anneal the studs for securing the blades, and if necessary, to renew them’. (To ‘anneal’ meant to heat the material and then allow it to cool slowly, which made it easier to work. In the event, it was necessary to renew at least some of them.)

Olympic’s Starboard Propeller Shafting

There was damage to Olympic’s propeller shafting, but Harland & Wolff did not think any bent shafting could be straightened out or repaired. Instead, it would need to be replaced:

The tail shaft can be withdrawn into the dock and so removed to the shop, the three pieces forward of this necessitate that certain plates should be removed from the ship’s side so as to pass them out into the dock and so send into the shop.

Where the shafting passes through [watertight] bulkheads, the plating has had to be cut in order to uncouple and pass the shafting to be removed through the orifice being cut in the ship’s side.

It is not expected that these four lengths will be in the shop for another seven or eight days, and so the renewal necessary as regards them is unknown. As a precautionary measure a forging has been ordered for one length of shafting. The shafting is hollow and Messrs. Harland & Wolff do not consider that if any length is bent it can be made serviceable by straightening.

The Titanic’s shafting is available if necessary but if used would entail considerable delay in that ship’s completion, as the engines are now being put into her.

While Olympic was in dry dock, Harland & Wolff took the opportunity to increase the pitch of her port propeller blades from 33 feet to 34 feet 6 inches. The cost was accounted for separately to the repairs of the collision damage. The new starboard propeller blades were undoubtedly set at the same pitch.